UGA Professor Finds Power in Partial Exodus

“Love your neighbor as yourself” is a lesson we learned from the Levite experience.

When I was a college student taking classes in Jewish studies, the quintessential question that came up time and again was about who wrote the Bible, the most read text of all time without a byline.

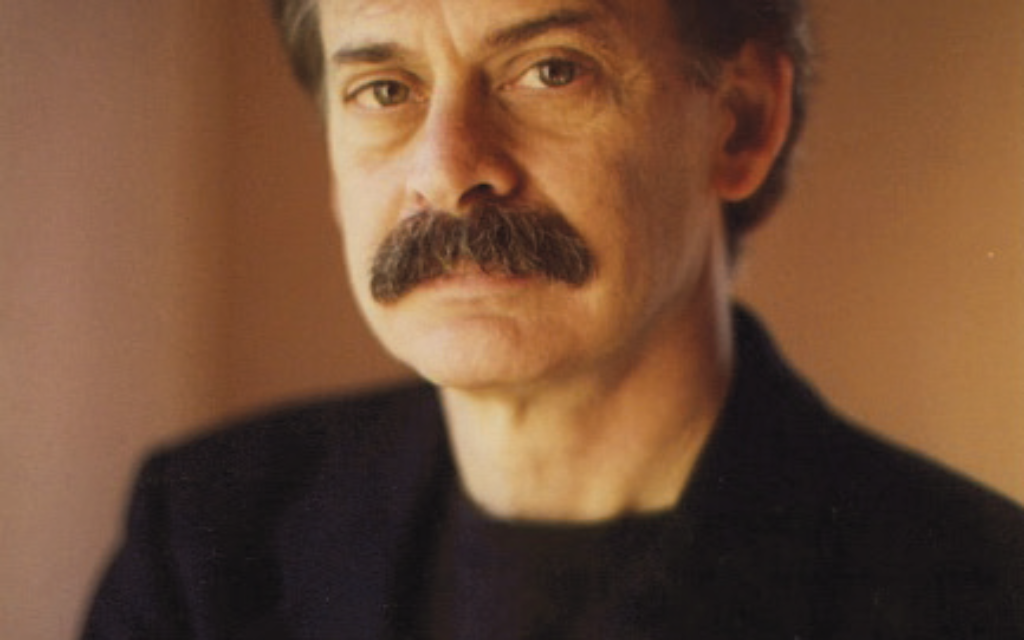

Biblical scholar Richard Elliott Friedman published a book in the late 1980s to answer that very question. “Who Wrote the Bible?” pieced together the contributions of multiple authors in various time periods, highlighting changes in voice and literary structure of the biblical text.

Friedman is known not only for his biblical investigative studies, but also for his ability to transmit biblical scholarship to lay readers in an accessible way.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

For the past 11 years Friedman has taught in Georgia, where he is the Ann and Jay Davis professor of Jewish studies at the University of Georgia. He spoke during Shabbat at the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism’s biennial convention in Atlanta, presenting his latest book, which came out in September: “The Exodus: How It Happened and Why It Matters.”

Friedman is a great storyteller and often sprinkles his teachings with humor and lightheartedness. He reminisced that his rabbi growing up presented the Exodus by saying that it doesn’t matter if the actual event happened; what matters are the lessons Jews have drawn from the experience.

Friedman joked that, living in the South, it would be incomprehensible to say that it doesn’t matter whether the Civil War happened, but what matters are the lessons we take away.

Intrigued by the challenge of grounding the Exodus in history, Friedman lays out evidence that makes the case for its historical validity, with a caveat. “Would it ruin your day,” he asked, “if you knew that the Exodus happened, but not everyone was in it?”

As he discussed at Congregation Shearith Israel in April 2016, one of Friedman’s main theories is that the Levites, who are the only ones in the Torah with Egyptian names, experienced an exodus from Egypt, while most of the Israelites were living in Israel at the time.

According to Exodus 12:37, the number of people leaving Egypt was 600,000 men, not counting women and children. With this figure in mind, we can assume the group fleeing into the desert totaled more than 2 million people.

Friedman, however, presents evidence from a multidisciplinary perspective of archaeology, biblical text study and genetics that the actual number of people leaving Egypt must have been significantly smaller.

One of Friedman’s textual arguments is based on a reading of the Song of Deborah, which is set in Israel and lists all the tribes of Israel without mentioning Levi. Alternatively, the Song of Miriam, or the Song of the Sea, which is set in Egypt, talks about “a people” leaving Egypt, without using the word “Israel.”

Lastly, there is the issue of the different names for G-d used throughout the text, which Friedman said is the clue that points to the multiple authors of the Torah.

Friedman’s theory is that the Levites, a genetically diverse group distinctly different from Egyptians, experienced an exodus out of Egypt and brought their narrative and their way of worship to Israel.

While our traditional view of the Exodus as an event experienced by all Israelites is challenged by Friedman’s findings, he said the moral lessons of the story are even more poignant when grounded in historical evidence.

Biblical texts associated with the Levites address how to treat “the stranger among you” and how to treat slaves with fairness. It is from those lessons that we get “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), which is solidified in the very fabric of Jewish consciousness.

Those lessons are not just moral fables. Friedman believes that they are based on the historical experience of the Levites and transmitted by generations of Jews in the annual retelling of the haggadah.

comments