Trapped in Atlanta’s Jewish Heroin Triangle

Atlanta has a Jewish heroin triangle and it's just as big a problem in the Jewish community as in the general community.

Editors Note: This story is part of a special report on Atlanta’s Jewish Heroin Triangle. See the rest of the coverage here.

In March I sat in a Sandy Springs home with three of five Jewish mothers who have children buried within feet of each other in the Menorah Garden at Arlington Memorial Park. All ages 20 to 31, those children died within two years of one another from causes related to opioid addiction — in all but one case, heroin.

As kids they attended public, Jewish and secular private elementary, middle and high schools. They had b’nai mitzvah celebrations. They went to Jewish summer camps.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

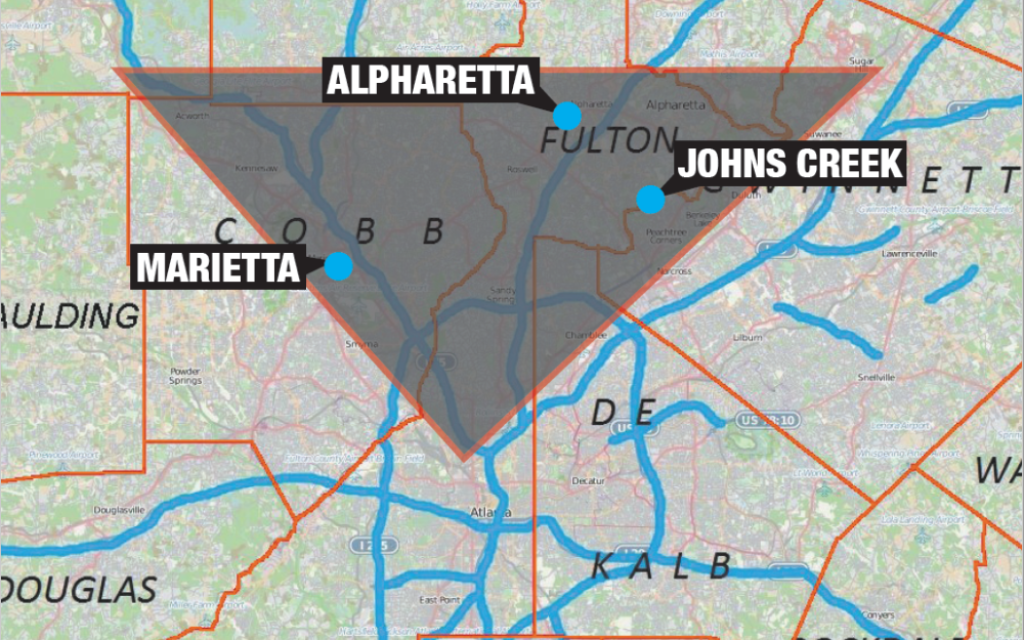

They all lived within what is now known as Atlanta’s Heroin Triangle, an area starting in northern Atlanta, running northwest past Marietta, then east through Alpharetta to Johns Creek and Duluth and back southwest, encompassing Dunwoody and Sandy Springs. It includes parts of Cobb, Fulton, Gwinnett and DeKalb counties.

In “The Triangle,” an 11Alive investigative web series in February and March, reporter Jeremy Campbell uncovered a 4,000 percent rise in heroin-related deaths from 2010 to 2016 in those affluent northern Atlanta suburbs.

The exposé shed light on a problem plaguing U.S. cities large and small, and inspired the National Prescription Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in downtown Atlanta on March 29, which President Barack Obama attended.

The series spawned the station’s follow-up “Inside the Triangle” reports, and it compelled the three mothers to share their stories.

One mom called to tell me Atlanta has a Jewish heroin triangle as well. Four years after losing her child, she wanted to speak out. She said there is a story here, a Jewish story, and it needed to be told.

Although all preferred to remain anonymous, three of the five mothers spoke with me that day in late March. All of them are permanently changed, their hearts broken by their incomprehensible loss.

I asked them what they wanted to say and what they needed the Jewish community to know. Their answers:

- Atlanta has a Jewish heroin triangle.

They all said heroin is just as big a problem in the Jewish community as in the general community, and it must be fully acknowledged. They want to dispel the myth that heroin addiction, untimely death and inexplicable loss don’t happen to Jewish people.

“We want the Jewish community to be aware that there is a drug problem among the Jewish community,” one mom said. “Young Jewish adults are dying. We are not immune to this public health crisis.”

- The regret, shame and stigma are almost unbearable, but no one is immune.

This is a club no one should ever have to join. But some do.

The mothers feel that they could and should have done more. They are aware that others must think they are terrible parents because drug deaths don’t happen to Jews, but they would have done anything for their children.

In addition to losing their children, they feel as if they lost their friends and community as well.

One said, “We want people to know that we’re not bad parents, and our children weren’t bad children.” Another added, “And we don’t want this to happen to them.”

The first said, “Heroin is not like any other drug. You can’t get off.”

She said most kids trying heroin for the first time don’t know “how potent it is, and once the drug takes a hold of you, you can’t get out of the vicious cycle. Heroin and opiates are poison. Drug dealers are murderers. They prey on the weak.”

- You can lose your child even when you are seeking help.

Shana was enrolled at a California treatment facility when she died of a prescription overdose in mid-2011. Her mother was due to fly to see her the next day when the coroner called to say she had overdosed on a combination of two drugs and was gone.

The treatment center had let Shana leave. Afterward, no one from the facility even called the mother.

A victorious judgment in a wrongful-death lawsuit, which paid enough only to cover attorneys’ fees, was little consolation. It did not bring Shana back.

Shana’s mom said other drugs, used over time, were the gateway to the more dangerous, ultimately deadly substances. She emphasized the common statistic that 45 percent of people who become addicted to heroin start out with prescription opioid pain pills.

Explore: HAMSA Helps Jewish Community Battle Addiction

- Low self-esteem is a factor.

One young man’s downward spiral began with a DUI conviction. Even on supervised probation, he could not stay clean, and he ended up in a rural Georgia jail for more than six months.

He then was sentenced to two months at a Tennessee halfway house, requiring this Jewish young man to attend church three times a week. Two weeks later, under family supervision at home, he overdosed in his bedroom.

“Each time, he couldn’t stay clean,” his mother said. “He used to cry to me that all he wanted was his life back — life before drugs.”

She added, “All of these kids wanted to stop, but you just can’t stop.”

The moms mentioned stress and depression as contributors. All three said low self-esteem and the feeling of no longer fitting in with peers became factors for their children.

- Addicts lie.

One mother spoke of how smart her child was. But, she added, “addicts lie. … They’re functioning, and you don’t even know they’re on it.”

A truism across all forms of addiction: Addicts will lie and steal to support their habits.

- You just don’t see it coming.

One child was a straight-A student in her third year of college when she succumbed to peer pressure.

Her mom said: “Life now? There’s not much life now. G-d hands you this beautiful, perfect child, and then they are gone, and you don’t know why.”

- We need a stronger Jewish presence in recovery in Atlanta, as well as additional narcotics-specific resources to battle heroin addiction in our community.

In reference to the many addiction programs, rehab approaches, recovery facilities and family support groups that are spiritual or faith-based, the three mothers said none felt comfortable, and most felt foreign to them and their families.

They see a need for Jewish support and resources at an affordable halfway house for the period after rehab so young adults can live together, share common experiences, get jobs and learn again to navigate life.

Affordability is a factor. Insurance typically covers the 30-days-clean rehab process, but a halfway house for that next crucial period can be cost-prohibitive. Ideally, the program should be specific to narcotic recovery because heroin addiction is so different from alcohol abuse.

The same holds true for Jewish-based narcotic abuse and grief support groups because the path of stigma, shame, guilt and loss traveled by the families of opioid addicts is very different from the journey of alcoholics’ families.

“Other people have their G-d or Jesus,” one mom said. “I don’t know what Judaism has. We have nothing. It’s a hushed society.”

Another said: “I don’t believe in G-d, in Judaism, now. There is no one helping spiritually. It’s not like alcoholism. There’s no shame to that. We need Jewish resources for fighting illegal drug use.”

- They want you to talk about it, and they want to hear from you.

Have conversations with friends, acknowledge the problem, “throw away stigma, embarrassment and anything else that gets in the way of finding help,” and join them in making an affordable facility and Jewish resources available here for addicts and their families.

In the spirit of the March heroin summit, regard opioid addiction as a disease, not a crime, so we can focus on intervention, and on saving our children.

“We know there are more that need help,” the three mothers agreed.

If you realize you know these women, please understand how difficult it was for them to lay themselves bare to increase awareness, inform us about Jewish Atlanta’s needs, and, they hope, spare others from the pain they have experienced. Don’t just talk to others about them; reach out to their families, thank them for their courage and offer to help in any way possible.

This article was written in loving memory of my bright, creative, sweet and beautiful niece, who left behind a hole in all of our hearts.

If you have personal stories, ideas or additional information for our community, please contact Leah R. Harrison at lharrison@atljewishtimes.com or 404-456-6208. Next week the AJT looks at new ways health care is dealing with opioids to prevent addiction.

A Jewish Place to Go

Three Jewish mothers interviewed for this article offer a wish list for the Jewish community’s response to opioid addiction:

- Regular but separate Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings held at synagogues or other Jewish facilities.

- A Jewish-friendly narcotics halfway house after rehab with psychological counseling and access to rabbinic support and Jewish services and observances.

- Jewish-based family and grief support groups.

Getting, Giving Help

If you or someone you know has lost a child and would like information on joining a support group, or if you want to help create a stronger Jewish support network in Atlanta to battle heroin addiction, contact Eric Miller, the program coordinator for HAMSA (Helping Atlantans Manage Substance Abuse) at Jewish Family & Career Services, at 770-677-9318 or emiller@jfcs-atlanta.org.

comments