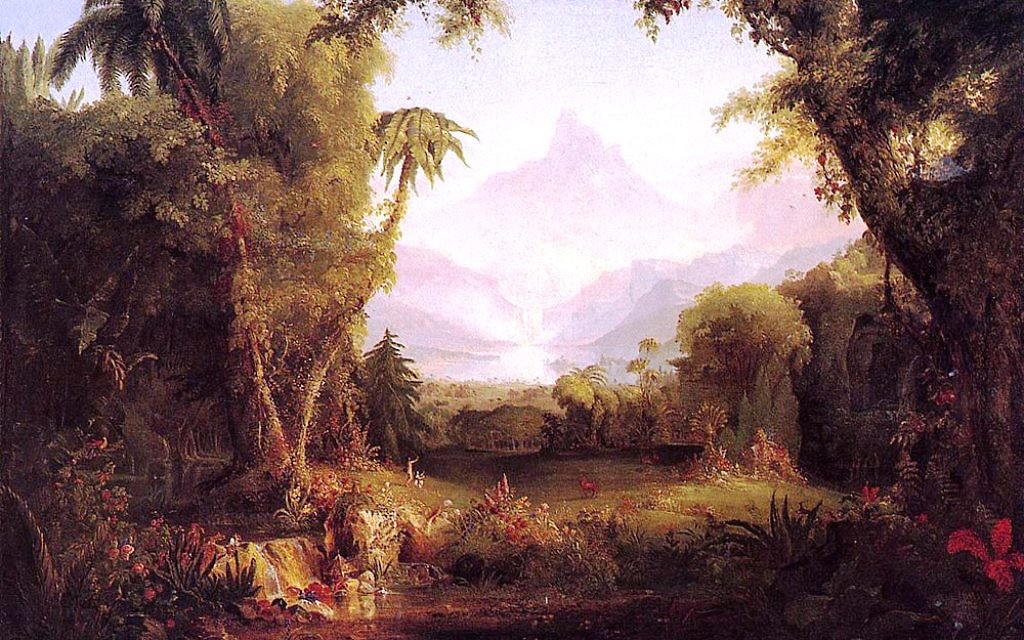

The Shul as an Inclusive Garden

More important than "Who is a Jew?" is "How can we share the beauty of Judaism?"

The glass is half-empty: Interfaith marriage is a crisis for American Jewry.

Demographers estimate that 40 percent of Conservative Jews who married between 2000 and 2013 wed non-Jews, and the figure was about 80 percent for Reform Jews. The calamity, as sociologist Steven M. Cohen has found, is that only 8 percent of the grandchildren of those intermarried couples consider themselves religiously Jewish.

The glass is half-full: Interfaith marriage is an opportunity for American Jewry.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

A decreasing percentage of non-Orthodox Jews are getting married, and those who do marry are typically waiting longer to do so and having fewer children. That’s where simple arithmetic kicks in.

If two Jews marry and have one child, the Jewish population declines, period. But if two Jews each marry non-Jews, and each couple has one child, the Jewish population can be maintained — as long as both couples raise their children Jewish, including conversion if necessary.

(It’s my thought experiment, so let’s ignore the reality that you need more than two children per couple on average to maintain a population. And let’s leave debates over the merits of matrilineal descent for another day.)

If those interfaith couples have multiple children, actual Jewish population growth is possible, as long as those families feel welcomed and want to be Jewish.

How the Jewish community should respond to interfaith couples is the topic for doctoral dissertations, but it’s an issue breaking to the surface again in the Conservative movement, which has resisted taking the Reform/Reconstructionist path of letting rabbis officiate at weddings between Jews and non-Jews. The Rabbinical Assembly bars Conservative rabbis from even attending such ceremonies.

A letter reasserting that position is expected soon from the Conservative leadership. You’ll have the chance to read the related thoughts of the head of the USCJ, Rabbi Steven Wernick, in a forthcoming AJT issue, and it’s sure to be a topic during the USCJ convention in Atlanta in December.

I had to drive three hours west to Huntsville, Ala., to hear an expert Conservative discussion of interfaith issues from an Atlanta resident, Rabbi Stephen Listfield, who was officiating at Yom Kippur services at Etz Chayim Synagogue for the third consecutive year. My son is a sophomore at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, and Etz Chayim graciously welcomed our family for the holiest day of the year.

Rabbi Listfield said he believes that the overwhelming majority of his fellow Conservative rabbis share his position: They should not officiate at interfaith weddings.

But he rejected the explanation offered by some colleagues that their role is to defend the boundaries between the Jewish and the non-Jewish.

In a world where most of us have non-Jewish relatives, Rabbi Listfield views rabbis’ job as tending the garden of Judaism so that it grows to be beautiful, vibrant and irresistible. After all, the challenge isn’t just to produce Jewish children; it’s also to engage those children and instill in them a love of Torah and Jewish identity.

One Jewish parent or two, we’re struggling outside the Orthodox world to create the necessary continuity.

Rabbi Listfield didn’t mention Chabad, but his preferred approach mirrors what you’ll find at Chabad. Although there are no fuzzy lines about who is and isn’t Jewish — if you weren’t born to a Jewish mother, you aren’t Jewish without conversion — everyone is welcome to pray, to learn and to share in the beauty that is Judaism.

That’s not a magic formula, and it won’t satisfy everyone. But it plays to Judaism’s strengths, and it offers a positive approach to a problematic opportunity.

comments