A Caliph’s Adviser and Religious Freedom Convey Past

Hasdai ibn Shaprut built foreign alliances in the 10th century; an Italian Jewish community thrived, thanks to a 1593 edit.

In this second article of our Sephardic Corner we will keep the promised format: First we will talk about a historical figure of Jewish Spain before the expulsion, then we will tell a story about one of the post-expulsion Sephardic communities.

Hasdai ibn Shaprut was born in Jaén, Spain, in approximately the year of 915 (his 1,100th birthday was celebrated in Jaén in 2015).

Hasdai studied Hebrew, Arabic and Latin and was fluent in the incipient Spanish of the time. It is interesting that only high-ranking Christian ecclesiastic authorities knew Latin.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

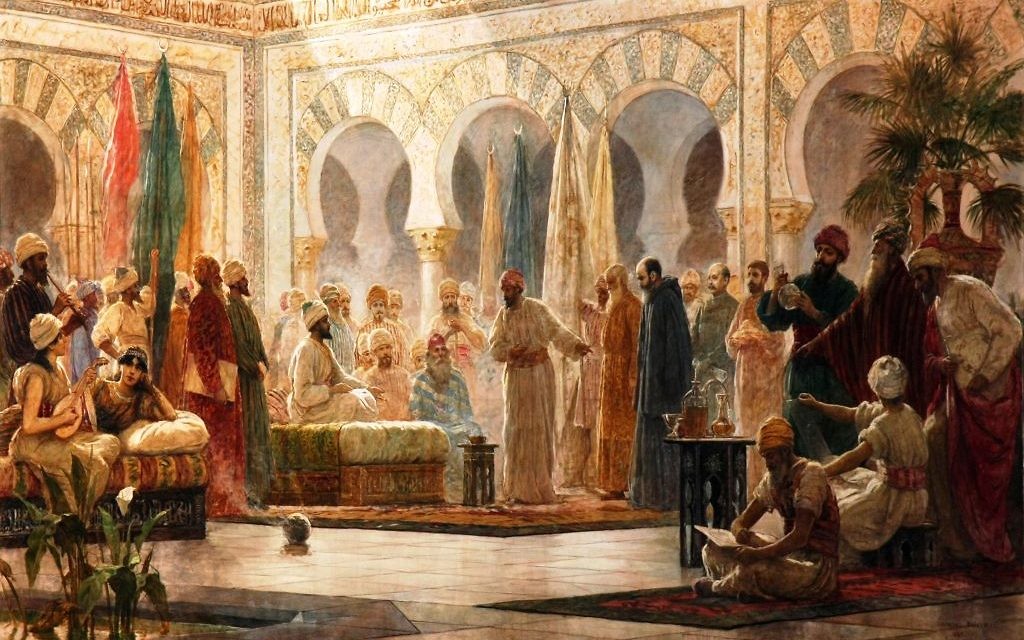

He also studied medicine and was named the physician for Caliph Abd-ar-Rahman III in Cordoba. He was one of the caliph’s principal advisers. Though he never received the official title of grand vizier (prime minister), he truly was in charge of foreign affairs. He established alliances between the caliphate of Cordoba and foreign powers and received foreign diplomats.

When Constantine VII, the emperor of the Byzantine Empire, brought a codex of the botanical works of the Greek physician Dioscorides as a gift to the court, Hasdai translated the work to Arabic.

Hasdai became indispensable to the caliph, given his cosmopolitan nature and his knowledge of languages and cultures. When the German king Otto I sent a diplomatic mission, led by John of Gorze, to Cordoba in 956, the caliph was afraid that the king’s letter would have words that could be offensive to Islam. He gave Hasdai the task of revising the letter to remove all content that could be offensive to the Muslim faith.

John of Gorze said he had “never seen a man with such a keen intellect as the Jew Hasdeu.”

Hasdai maintained relations with several of the rabbinical schools of the Middle East, such as Sura and Pumbedita. He fomented rabbinical studies in Cordoba by naming Moses ben Hanoch from Sura as director of a yeshiva, contributing to an independence of Western Jewish thinking from Babylonian influence.

Another historical fact deals with the difficulties that arose between the Spanish kingdoms of León and Navarra. Sancho I of León had been overthrown by followers of his cousin Ordoño IV. Thanks to Hasdai, Sancho’s grandmother Queen Toda of Navarra approached the caliph for help in recapturing the throne for her grandson.

Sancho, whose obesity did not allow him to ride a horse — essential for a leader — was cured by Hasdai of his paralyzing condition. Eventually Sancho was restored in the throne, and the caliph received 10 castles as compensation.

Hasdai intervened before Empress Helena, daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Romano I, to defend a Jewish community in southern Italy that the emperor wanted to convert to Christianity by force.

He spent years trying to communicate with the Khazars, who lived north of the Black Sea, believing that they were one of the lost tribes and the only free Jewish state. Later he learned that they had converted to Judaism and were not the representatives of Jewish continuity that he had thought. He maintained communication with them and informed them about the Jews in the West, although shortly after they were defeated and eliminated.

Now we will talk about one of the Sephardic communities formed after the expulsion, the community of Livorno (Leghorn) in Italy. Sephardim arrived in this port city because of the edict known as La Livornina, promulgated by Ferdinando I of Medici in 1593, which created the free ports of Pisa and Livorno.

Some of the edict’s clauses were radical in the context of the time. For example, Ferdinando promised to “free you as people, to free your merchandise, clothing and families, your Hebrew books or those printed in other languages or handwritten. We guarantee that during the period stipulated no Inquisition, reconnaissance visit, denouncement or accusation will be made against you or your families, even when in the past you have lived outside of our domain as Christians or pretending to be so.”

The Jews in Livorno opened their first printing house 1650 and published in Solitreo (a cursive form of Ladino or Judeoespañol using the Hebrew alphabet).

The Spanish-Portuguese Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the 15th century reached an economical and cultural development in Livorno that was rarely equaled in other Jewish communities worldwide. They could practice Judaism without fear of the Inquisition, were free to study and obtain university degrees, to own real estate, and to live in any part of the city (there was no ghetto).

They could enter and leave the city at will, print their own books, and carry out justice autonomously in quarrels between Jews. The Jews of Livorno became commercial intermediaries between Levante, Italy, and northern Europe and were guaranteed diplomatic protection in the exterior.

Thanks to the edict, the Sephardic community of Livorno became one of the most important centers of Judaism of the time, explaining the influence of the Livornesi-Jewish presence in the Mediterranean. Sephardic merchants were active in coral, spices and medicines, introduced soap making, and installed looms for silk and wool weaving.

The Jewish population in Livorno grew until it became the biggest Jewish community of Italy by the 18th century, a total of 10 percent of the city’s population. The climate of tolerance and freedom made Livorno famous for the continued existence of a Jewish community for more than three centuries.

The Livornesi Jews were polyglots, and in their community life they used many languages: Hebrew was the sacred language, and, until the Napoleonic era, they used Portuguese for official community acts and in the merchant activity with other Sephardic communities. Spanish was the language of the literary texts, and Italian was used to communicate with the surrounding society. They also spoke Bagito or Bagitto, a mixed Jewish-Livornesi language based on Italian but with other components, including Yiddish.

By 1700, this community’s fame was such that rabbis from the East and the West came to Livorno to study at the Talmudic academies. Famous rabbis such as Malachi’ Accoen, Abram Isaac Castello, Jacob Sasportas, David Nieto, Chaim Josef David Azulai, Israel Costa and Elia Benamozegh lived and studied in Livorno.

There also was an influx of poor Jews, usually from Central Europe, who searched for better conditions. Among some world-famous Livornesi Sephardic Jews are the painters Serafino De Tivoli and Amedeo Modigliani; the educator Sansone Uzielli, the comedian Sabatino Lopez, the writer Alessandro D’Ancona, and the mathematician Federico Enriquez.

comments