Standing at the River’s Edge

It's nice not to be alone when you must observe life's transitions.

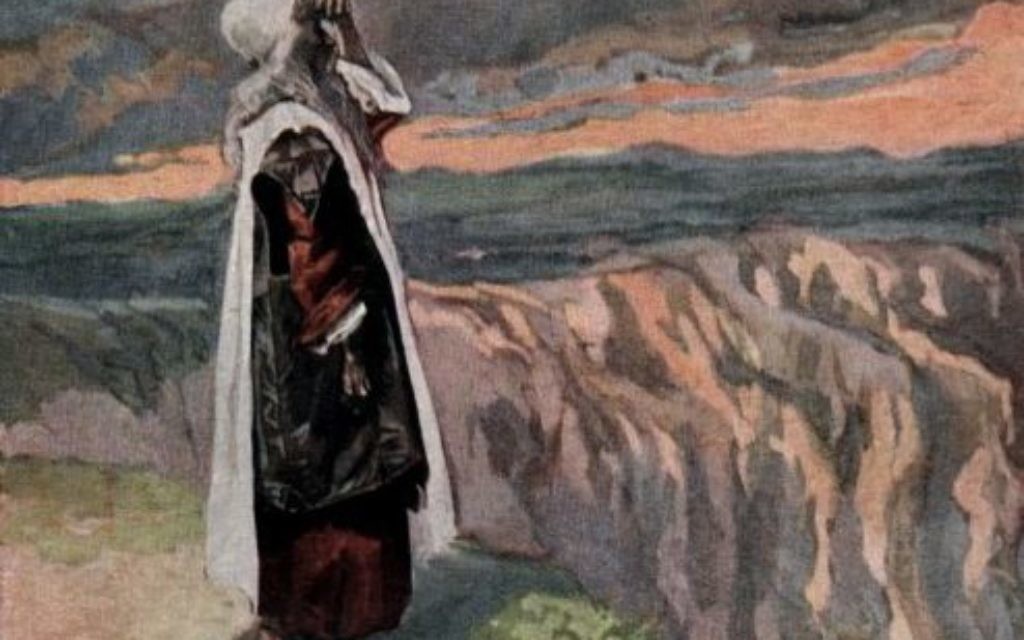

Moses guided the Israelites out of bondage and through the desert, encouraged them in their despair and chastened them for their wickedness, and yet the Divine barred him from crossing the Jordan River into the Promised Land.

Consider this as an allegory.

We parent as best we can, aware that we make mistakes. Along the way, there are lessons to learn: We must let our children fall so that they learn to pick themselves up, we cannot take on their pain, and there is nothing we can do to remove the hurt of a heartache, a defeat, a rejection.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Yet, after all these labors, we must stand at our own river’s edge and watch them cross alone (translation: help them set up a dorm room or apartment, then be invited, ever so gently, to give them a hug, a kiss, a wave — and leave).

Our offspring must proceed alone, taking with them all of the hard-earned wisdom we have tried to impart and without all that we wish we had said and done to that point.

We eagerly await reports about their lives outside our embrace (even if they remain inside the I-285 Perimeter).

By happenstance, the Jewish calendar placed Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11, also known as Va’etchanan (“and I pleaded” in Hebrew), as the parshah ha’shavuah, the Torah portion for the week, when our congregation held its annual service to honor young men and women beginning the next phase of their lives after high school.

This is a popular service, as many members have known these young men and women since they were small children. Boxes of tissues were passed around in advance.

This year’s service was personally affecting, as our 18-year-old son, the youngest of our three children, was among those being sent off with blessings.

The irony of Moses’ story — being allowed to look over but not cross the river with his flock, realizing that his days as their leader were ending — was lost on no one present, particularly the parents.

The rabbi, whose tenure began about the time these young people were born, told them that no matter how far they travel, the congregation will be there for them.

The congregation gifted each with a set of travel-size Shabbat candlesticks.

This is a time of transition, for both these teenagers and their parents (particularly for those whose homes will be noticeably quieter in their absence).

I have come to appreciate our congregation’s custom in handling another of life’s transitions.

When Kaddish was chanted in the synagogue where I grew up, the entire congregation rose, and those in a period of ritual mourning or observing a yahrzeit became indistinguishable from those around them.

I also have visited congregations where only the mourners stand, visibly isolated in their grief.

Our custom is that, at the beginning of Kaddish, the mourners rise.

Yit’gadal v’yit’kadash sh’mei raba

b’al’ma di v’ra khir’utei

v’yam’likh mal’khutei b’chayeikhon uv’yomeikhon

uv’chayei d’khol beit yis’ra’eil

ba’agala uviz’man kariv v’im’ru

We may sympathize, but we cannot fully comprehend their loss.

But when we get to this line — Y’hei sh’mei raba m’varakh l’alam ul’al’mei al’maya — the congregation rises and prays with them, in effect saying, “We recognize your grief, and we are here for you.”

When my father died five years ago, during the shiva in our home, I stood, with my wife and children and our rabbi, feeling the pain of my loss, and began to recite Kaddish.

When we came to that line — Y’hei sh’mei raba m’varakh l’alam ul’al’mei al’maya — and all those present, including fellow congregants and friends, stood up, I felt an energy, almost as if I were being propped up.

Every time since, when I rise during Kaddish, I remember that feeling and the comfort of that support.

When you come to paths that you cannot follow or must walk alone, some wistfully and others in grief, value the presence of those who stand and say, “We have been there, and we are here for you.”

comments