Radow Lecture Provides Understanding on Terrorism

Robbie Friedmann explains the motivations behind terrorism at the annual Paul and Beverly Radow Lecture.

Responding to terrorism involves a clear understanding of the perpetrators, ideological shifts in the Middle East and other developments in the region, the founding director of GILEE, Robbie Friedmann, explained during the annual Paul and Beverly Radow Lecture at Kennesaw State University on Wednesday, Oct. 25.

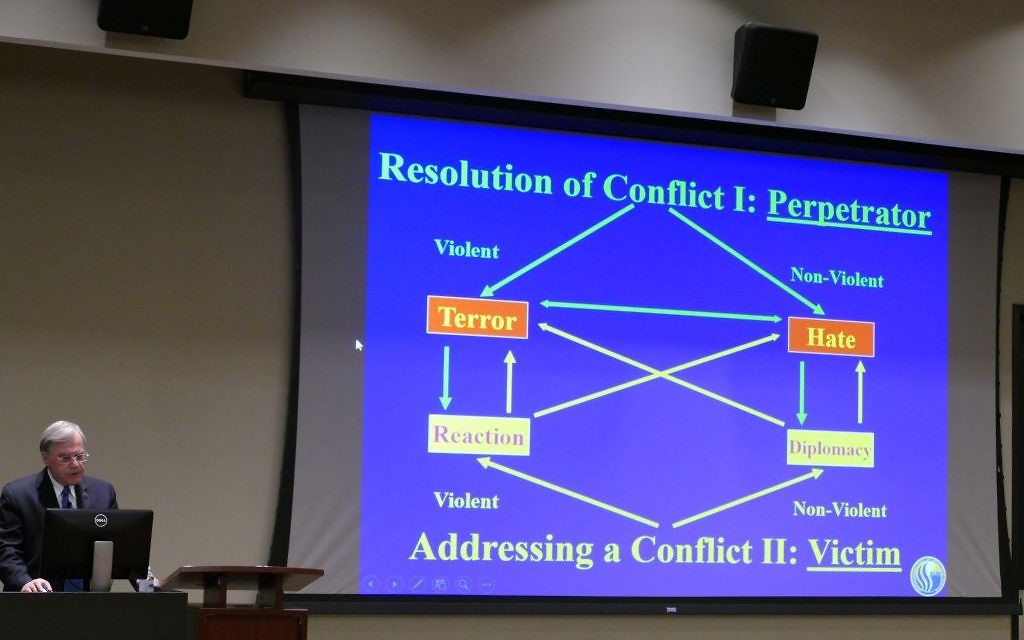

Friedmann, whose Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange program at Georgia State University includes anti-terrorism training for U.S. police in Israel, offered three ways terrorists use to solve conflicts: nonviolence through hate, violence through terror, and retaliation from the victim using either.

“For example, diplomacy may have an outcome that may lead to hate, and that hate may lead to terror and cause what we know in military language as asymmetrical warfare, not through tanks and weapons against equal powers, but by a single person or a group of individuals who create havoc because of their ability to do so,” he said.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Terrorism can be divided into terrorist-inspired activities and terrorist-initiated activities, the latter referring to attacks such as 9/11, Friedmann said. “It’s mental illness, attitude problems, loneliness or depression — that’s the image the media portrays,” he said. “However, law enforcement and politicians are reluctant to call it a terrorist event because it may have political ramifications.”

To understand terrorism, Friedmann said, people must first grasp its intent.

A perpetrator can target someone with nonviolent hate, which leads to vilification and demonization, followed by dehumanization, incitement and inevitably a plot to kill. “This is exactly what the Nazis did against the Jews,” Friedmann said. “They defined the Jews as subhumans and came to the implication and conclusion that if they are such, it is legitimate to exterminate them. However, the danger is that incitement legitimizes hate-based ideology, which leads to violence.”

He said terrorism includes wars as well as individual events that make the news.

Although conflicts in the Middle East date back at least to the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, in which Britain and France carved up the post-Ottoman region, “the threats are now different because Iran is seen as a danger not only to Israel and Saudi Arabia, but to Jordan and is perceived to control large chunks of Iraq, Syria and Lebanon,” Friedmann said. “Iran is a major power that has its hands everywhere and the ability to disrupt the region.”

He said it’s a mistake to overlook conflicts among Muslims and among Arabs. “Suffice it to say there have been more Muslim victims of war and Muslim terrorism than any other part of the world.”

Friedman noted the more than 600,000 people killed in Syria’s civil war since 2011.

He emphasized that Islamic radicals and fundamentalists do not compose a majority of the Muslim population. “I’m not sure if we can talk about the majority of the Muslims because there are about 1.5 billion Muslims, or a quarter of the world’s population, and to suggest that a Muslim in the Middle East is the same as a Muslim in Malaysia, India or China is simply wrong.”

He said Osama bin Laden’s legacy among jihadis is the idea that “oil is a perishable commodity which the Arab world has, and when in 200 to 300 years it is no longer available, no one will have it, including the West, which will destruct itself.”

Islamic State, an offshoot of Al-Qaeda, dreams of a world caliphate, Friedmann said. “Although they may not be doing well militarily, the ideology is still there.”

While religion plays a role in terrorism, Friedmann suggests that anyone who knows anything about theology or religion should avoid that debate.

“I’m not sure most of us understand our religion well enough and doubt we would understand the religion of others,” he said. “It’s simply not a smart tactic.”

Friedmann also spoke about global aspirations among countries and tectonic shifts in today’s world order. He noted that Bin laden called for a caliphate from Andalusia to the Philippines because Spain represented a golden era of Islam.

He said the West’s preoccupation with Iraq and the Palestinians often diverts attention from strategic goals involving Muslim regimes, such as Iran.

Between 2010 and 2017 there were about 30 terror attacks a month, said Friedmann, who believes that incitement is a key factor.

“We do not have a red card for terrorism,” he said, using a soccer analogy. “We somehow live with it, and I think that we are missing the goal against terrorism. Just because I am not armed and I don’t know how to fight does not mean I do not pose a threat. I think that is an area of legitimacy, which needs to be questioned.”

He added, “I think it’s fair to say that terrorism begins with the indoctrination of hate” and requires a counter-terrorism response, “which does not mean more machine guns and better security, but may be necessary to dismantle the terrorist infrastructure, to cope with the terrorism ecosystem and show zero tolerance toward indoctrination that causes it to thrive.”

comments