Music as Midrash Shapes Reform Worship

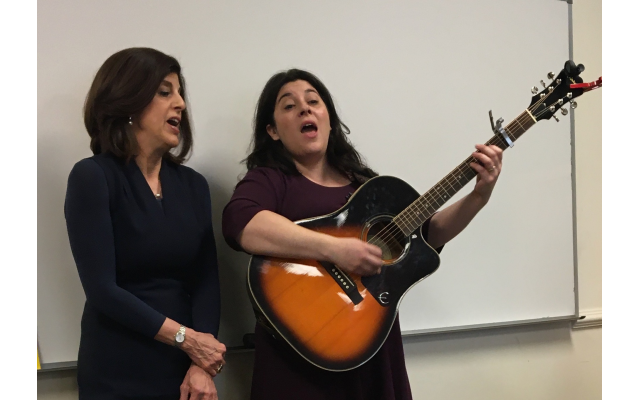

Reform Judaism’s focus on a more personal and participatory musical worship experience was explored earlier this month at The Temple in Atlanta.

Reform Judaism’s focus on a more personal and participatory musical worship experience was explored earlier this month at The Temple in Atlanta. Elana Arian, who performs frequently before Reform congregational audiences around the country, described the experience as “musical midrash,” the process of putting new melodies to traditional words of prayer.

Traditional midrash is the way Jewish rabbis and scholars search for contemporary meaning in familiar religious texts, but according to Arian, music can create new meanings as well.

“The putting of a melody to any form of prayer is a kind of midrash,” she said at her Feb. 1 appearance. “We know there are many different ways to pray, but the first person to say we could feel that prayer more if we could sing it, was creating a midrash. Every melody is in fact an interpretation of that form of liturgy.”

More personal and interpretive forms of midrash in Jewish worship were slow to catch on, particularly in large and influential congregations like The Temple, where stately melodies performed by a classically trained cantor and carefully rehearsed choir were the norm through much of the 20th century.

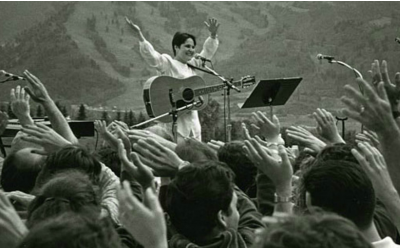

That all began to change in the 1970s, under the influence of composers and performers like Debbie Friedman, who was strongly influenced by the folk revival in youthful popular music in the 1960s. She combined lively, memorable and often accessible melodies that could easily be sung by worshippers with traditional Hebrew liturgy and original lyrics in English.

According to Arian, that new sense of informality didn’t always sit well with more conservative congregants of the time.

“The accepted cantorial style then was meant to bring us to a really elevated place, a place on a higher plane. There’s really a place for that in our worship,” she said, “however, when Debbie Friedman started to create her own melodies for prayers, you can imagine what people thought of that. People were very threatened by that idea, like, how dare you.”

Gradually, Friedman’s musical midrash approach, which spoke to both the intellectual and emotional traditions of Judaism, began to win converts. Under the influence of a new generation of cantors, who, beginning in 1975 included sizable numbers of women, the emphasis began to shift away from performances admired for their form and beauty to more direct forms of participation in worship.

“Debbie would answer this question of why are you composing a new melody for something we already have with her idea of music as midrash,” Arian pointed out. “Every melody for every essential piece of text that you have was a midrash by that composer. For Debbie, it was a foundational idea of her work and gave rise to an entire generation that reinterpreted text that was quite old and made them feel new.”

Friedman was particularly influential in making prayers of healing an important part of the modern American Jewish worship tradition. Her melody and interpretation of the “Mi Shebeirach” healing prayer was adopted by numerous congregations, regardless of their denominational affiliation and is said to have revitalized the offering of prayers for recovery from illness.

Under the impact of her influence, forms of worship that expressed a more emotional vulnerability and openness became the standard in Reform Judaism.

Friedman told an interviewer for JewishTVNetwork.com, posted on YouTube soon after her death in 2011, that her midrash was written about the words before the recitation of the “Amidah” (silent, standing prayer) and spoke most directly about how she saw her work.

“G-d, as I stand alone,” she wrote of the midrash, “I pray my heart will sing out to you so many thoughts and fears that I have. May I open my lips in prayer.”

For Arian, who came to know Friedman well before her untimely death, she was a family friend and mentor whose influence was personal.

“She taught that to get connected to the words of the liturgy is to make them live in our own mouth and in our own body. So it’s not just about the realm of G-d and what G-d does, but about what we do.”

For the musical followers of Friedman, the battle of the future direction of Reform Judaism is largely over. Except for special holiday services, such as those on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the classical tradition in worship has largely faded.

That was one of the ideas behind the documentary, “A Cantor’s Head,” featured at the just-ended Atlanta Jewish Film Festival.

But for Arian and for many who revere the influence of the musical midrash that Friedman brought to Jewish sacred music, that was all for the good.

“We are always stronger when we open the doors more,” she emphatically suggested. “As a people we are always stronger when we open and open and open the doors.”

comments