Living by the Golden Rules

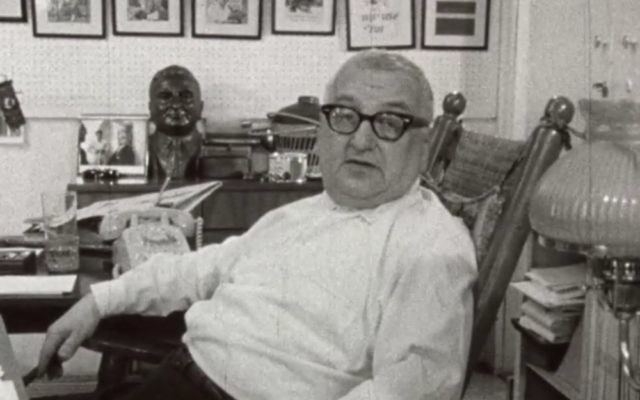

Above: Harry Golden

By Rebecca McCarthy

Writer and humorist Harry Golden liked to say the Jewish community in Charlotte thought he was a nut because he was the only Jew who didn’t open a store after moving there from New York in the early 1940s.

Instead, he created and ran a Jewish newspaper, The Carolina Israelite, for almost four decades, writing about everything from hot dogs to politicians to his childhood in the Lower East Side of New York to civil rights. He also wrote best-selling books, including “A Little Girl Is Dead,” which reopened the Leo Frank case after half a century.

He also enjoyed the friendship of Carl Sandburg and Billy Graham and became a strong civil rights advocate and a regular celebrity guest on late-night television shows.

He was funny, irreverent and intelligent, always advocating for the underdog.

Journalist Kimberly Marlowe Hartnett of Portland, Ore., recently visited the University of Georgia Richard Russell Special Collections Libraries to tout her book, the first complete biography of the cigar-chomping, bourbon-loving writer, “Carolina Israelite: How Harry Golden Made Us Care About Jews, the South and Civil Rights.”

She talked about Golden and showed snippets from a documentary, made by UGA filmmakers in the 1970s, about Golden, his life and his work. The Walter J. Brown Media Archives has made the documentary available to everyone.

The 1966 UGA movie shows Golden to be a droll, charming wit. He takes us to his old neighborhood and into the apartment building where he lived as a child with his parents and siblings. The names on the mailbox had been Irish, he says, then became Jewish and are now Hispanic. He turns to the camera and says such changes are American and signal mobility.

Hartnett, who has worked as a reporter for newspapers in New England and the Northwest and is the communications manager for a Portland nonprofit, told the UGA audience that Golden wanted the movie audience to believe the stories he told on camera were spontaneous, but he was relating stories he told well and regularly.

Golden was born Herschel Goldhirsch in Ukraine and came to New York with his parents in 1907. His older sister worked on Wall Street as a stockbroker in the 1920s, when everyone in America, it seemed, was a speculator. Harry followed her and made lots of money buying, selling and promoting stocks until the 1929 crash.

Afterward, he was convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to five years in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. When he got out, the Depression was in full swing, and he had a wife and three sons to take care of. He traveled the East Coast, selling advertorial copy to newspapers to keep grits and gravy on the table.

In 1940, he landed in Charlotte and never left, though his wife and sons stayed in New York.

Though Golden never talked about his incarceration, it came up after he published “Only in America,” with a foreword by Sandburg. He was contacted by someone who knew of his prison sentence and threatened to go public if Golden didn’t pay him.

But instead of giving in to the blackmailer’s demands, Golden owned up to his past, and sales of “Only in America” went even higher. Richard Nixon later pardoned Golden.

Golden “would have been a good blogger,” Hartnett said. She said Golden wrote briefly, simply and eloquently about the day’s topics. In doing so, he introduced blacks to whites, Jews to gentiles, Yankees to Southerners.

His tongue-in-cheek solution for segregated waiting rooms, segregated schools — any segregated setting where white people didn’t want to sit next to or even near black people — was to remove the chairs, an arrangement termed “the Golden Vertical Negro Plan.” His reasoning was that people would stand in line with anyone but sit only with someone of their own race. That solution has echoes of Jonathan Swift’s satirical “A Modest Proposal,” which advocated that Irish parents sell their babies as food to the British.

Golden didn’t have a James Boswell following him around and keeping track of his pithy conversation, but he became famous for delivering witty one-liners to newspaper and magazine reporters and radio and television talk-show hosts. And his essays often sparkled.

He called intellectuals “smart people with no charm.” Referring to 1964 presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, he said, “I always knew the first Jewish president would be an Episcopalian.”

Golden could be serious as well: Life magazine chose him to cover the beginning of the 1960 trial of Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Hartnett wrote a college thesis on Golden. When she was researching her biography, she learned that her mother really had worked for him in the 1950s, a story she had thought her mother exaggerated.

comments