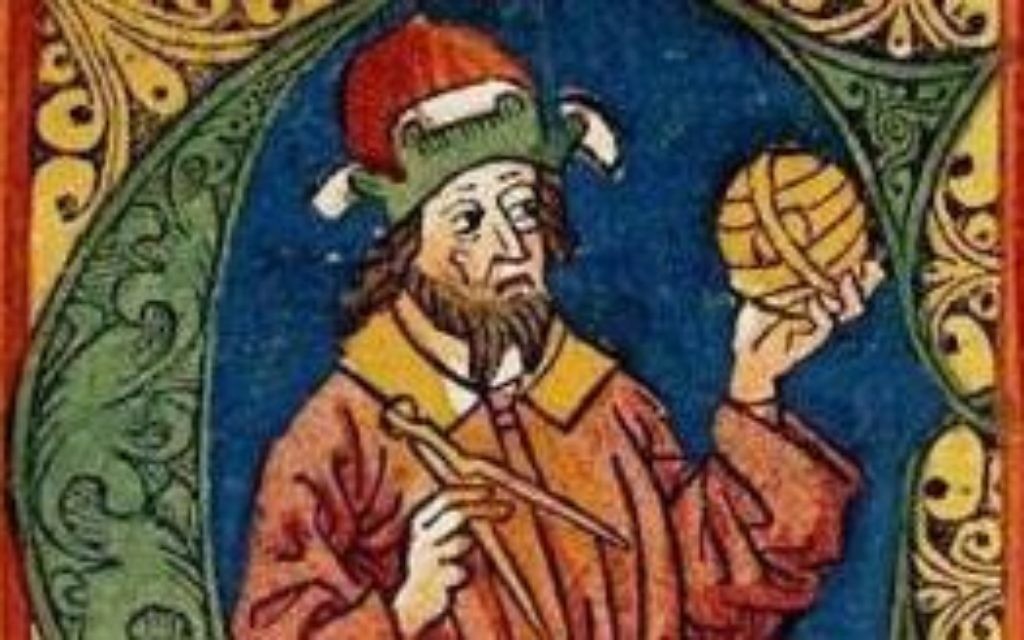

Ibn Ezra Personified Diaspora Wandering

Post-expulsion, Sephardim who settled in Livorno became the Syrian nobility.

Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra was born in 1092 in Tudela, Navarre, in the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula, and lived until 1167. He was a renowned biblical scholar, poet, mathematician and grammarian.

Ibn Ezra wrote “Ki Eshmera Shabbat,” a popular Shabbat dinner song known in all Jewish traditions.

Abraham ibn Ezra’s childhood, his schooling and his family are mysteries. It is known, though, that he began to travel throughout the Iberian Peninsula around 1119 and visited Cordova, Lucena, Granada and Seville. In his travels he met several illustrious Jewish scholars.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

From a comment made in his exegesis (interpretation and comments on religious works) of Exodus, it has been deduced that he was the father of five children. They probably died early, except his son Isaac, who left Spain.

Isaac converted to Islam, and with the purpose of bringing him back to Judaism, Abraham ibn Ezra abandoned Spain shortly after.

Isaac’s conversion was a severe blow to his father. When Isaac died, Abraham ibn Ezra expressed his grief in two moving elegies. We reproduce a brief example of one of them:

When I recall three years past,

His death among foreigners

And his vagabond life

And my longing for him …

Hold back, my friend,

If you comfort me, you bring me grief;

Do not make me recall the love of my life.

Unable to bring his son back to Judaism, Ibn Ezra did not return to Spain. Instead, in 1137 he traveled to North Africa and Egypt. He arrived in Italy in 1140.

The first fruits of his stay in Italy were a series of works on the exegesis of the Torah and Hebrew grammar. He is known to have been in the following cities: Rome (1140), Lucca (1145), Mantua (1145-1146) and Verona (1146-1147).

It is supposed that Ibn Ezra also traveled to Palestine and to Bagdad (tradition states that he went as far as India) at some time between his time in Italy and his stay in France.

Ibn Ezra moved in 1147 to Provence in southern France, where he was received with honor and respect. In northern France, in Dreux, he completed several of his exegetical projects and began a new commentary on the Torah. He is considered second only to Rashi in terms of the quality and impact of his exegesis.

In northern France, Ibn Ezra came into contact with Rashi’s celebrated grandson Rabbi Jacob Tam, and he wrote a poem in praise of his brother, Samuel ben Meir.

Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra then went across the channel to London, where a rich colony of enthusiastic Jews (before their expulsion in 1290) were eager to have this prestigious representative of Jewish learning in their midst.

In 1160 he appeared back in southern France, where he translated an astronomical work from Arabic. Yet before his death the rabbi wanted to return to Spain, and most scholars agree that he died in Calahorra, a city in the present-day province of La Rioja.

Abraham ibn Ezra wrote many books about astronomy, philosophy and mathematics. “The Book of the Number” describes the decimal system for integers with place values from left to right. In this work ibn Ezra uses zero, which he calls galgal (meaning wheel or circle).

Despite ibn Ezra’s books, his mathematical ideas would not become accepted into mainstream European mathematics for several centuries.

Ibn Ezra also made the first attempt to systematize Hebrew grammar.

To him, there was no conflict between science and religion. He considered science to be the basis of Jewish learning.

Unlike some of our protagonists, Abraham ibn Ezra was not wealthy. In one of his poems he wrote:

Were I a merchant of candles, the sun would not set until I died! …

Were I to trade in shrouds, men would not die in my lifetime! …

Were I to sell armaments, all enemies would be reconciled and not make war!

As an anecdote, the English poet Robert Browning wrote a poem dedicated to ibn Ezra that begins with the verses “grow old with me, the best is yet to be.”

John Lennon wrote a song called “Grow Old With Me” based on Browning’s poem.

Syria’s Jewish Nobility

Now we will describe another one of the Sephardic diasporas that followed the expulsion from Spain in 1492. This group of Sephardim, known as the Syrian nobility, descended from the Spanish Jewish nobility who settled in Livorno, Italy, after leaving Spain and Portugal (as discussed in this column in December).

Members of their families had been renowned philosophers, mapmakers, court advisers, bankers and astronomers. Many of them had been able to take their money, art and other wealth with them when fleeing from the Iberian Peninsula, despite a prohibition announced in the expulsion decree.

Around 1600, a group formed by members of this nobility sailed to Syria, where they found a small number of families who had lived in Aleppo since the destruction of the Second Temple, if not earlier. The Musta’arabin of Aleppo (native Arab Jews, as the Spanish called them) claim direct descent from King David through the Dayyan family of Syria, said to be living there since 70 C.E.

These Jews of Aleppo shared the Aleppo Codex, or Keter (crown) of Aleppo, with the Italian/Spanish Jews, whom they designated as the signoreem (plural of signore). Today, this Aleppo Codex is a famous rabbinical document and is well-known in the world of Orthodox Sephardic Jewry.

The Spanish Jews maintained Ladino (Judeoespañol) as their language, and the wealthier families could apparently buy protection and tolerance, although their lives were never perfectly secure.

The surnames of the noble Jewish families of the Spanish court include Ashkenazie, Azari, Blanco, Cohen, Franco, Garzon, Gomez, Levi, Lopez, Lobaton, Matalon, Mizraji, Salas, Setton and Tuleda.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, most Jews in Aleppo lived in the center of the old city in the Spanish culture enclave. There were synagogues in which the Spanish-Portuguese tradition was followed, while others maintained the Arab-Jewish tradition.

An anecdote from daily life concerns the Jewish cafe where the Sephardim would go to listen to a Spanish-Jewish musical ensemble composed of a singer, stringed instruments and drums. Often the entire family attended this cafe to conclude a business deal, and the arranged marriages were frequently decided at this venue.

The most popular refreshment (orange blossom custard topped with cold fruit marinated in raisin wine) was named Morena me Llaman, just like the popular Sephardic cantiga (song).

The Sephardic Corner is a monthly contribution of Congregation Or VeShalom to the greater Jewish community.

comments