How Fear of a US Retreat from the Mideast is Driving Netanyahu Toward Annexation

Why the prime minister is still pushing to apply Israeli sovereignty to parts of the West Bank, despite legions of critics and even disquiet in the White House.

Why is Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu so keen on annexation? Theories range from the psychological — he’s seeking a legacy — to the political — to distract the public from his corruption trial — to the ideological — he’s an expansionist ideologue empowered by a right-wing American administration.

Some have spoken about the “window of opportunity” represented by the remaining months of the Trump presidency — assuming, as most Israelis do, that Donald Trump is not reelected.

That sudden advantage for the anti-Israel side could have a real effect: hurting Israel’s diplomatic standing and weakening its regional alliances, International Criminal Court investigations of some Israeli officials, political isolation and even the threat of economic or diplomatic sanctions, a prospect made more dire by an economy already ravaged by the coronavirus.

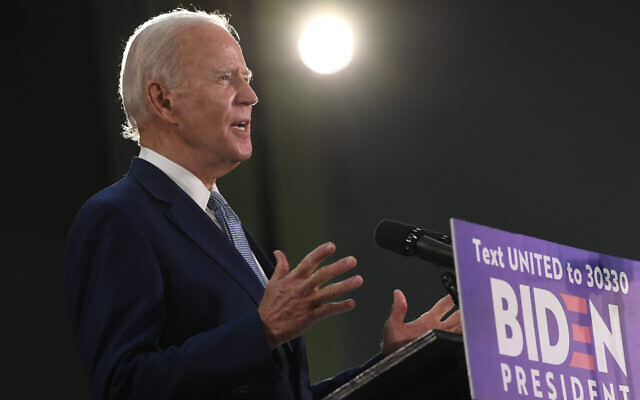

Given the high potential costs, none of the usual run of explanations seems adequate. Even the “window of opportunity” theory is hard to understand. An annexation amounts to an Israeli declaration about the status of some territory. Trump may recognize that declaration, but would a President Joe Biden uphold that recognition in six short months? And if the latter does not recognize the declaration, what has Israel achieved by making it? Does it matter that even the Trump White House seems less than thrilled?

Netanyahu has done an exceedingly poor job explaining his thinking, which may be responsible for the proliferation of theories trying to explain it. There’s also the fact that his insistence on such a dramatic step is wildly out of character for the prime minister, who has built his reputation and much of his popularity over the last decade on his overriding caution in matters of land, peace and war.

If the benefits seem elusive and the potential costs high, why now? Why pursue a policy so vehemently opposed by many Democrats and now so closely identified with a Republican administration unlikely to survive the November race?

When Israeli defense planners who support an annexation move talk about a “window of opportunity” in Washington, they mean something larger than the expected end of the Trump presidency. There is a fear that America itself is in retreat, and with it a global order that could be relied upon to ensure some measure of stability and security for a small country like Israel.

“American hegemony is crumbling before our eyes,” said Dr. Eran Lerman, a prominent conservative defense thinker who supports the annexation plan, when asked by The Times of Israel this week why Netanyahu seemed so bent on the idea. Lerman is a grizzled veteran of such Israeli debates and an important voice in the conservative camp. After 20 years as a top analyst in Israel’s military intelligence directorate, Col. (res.) Lerman became a deputy national security adviser to Netanyahu and the National Security Council’s point man on foreign policy. He is now vice president of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security (JISS).

It is hard to exaggerate the effect that the sense of American retreat has on Israeli thinking. Even if the rumors of general American decline are exaggerated or premature, Washington’s retreat is more acutely felt in the Middle East because of the American pivot toward the Pacific and the strategic challenge of China. That is, the retreat here — the drawdown of troops and capabilities from the Middle East and Mediterranean and a growing unwillingness to engage and police — is a willful strategic choice. Neither a Republican nor a Democratic administration is likely to re-prioritize the Middle East in the foreseeable future.

A great deal of annexation’s downsides amount to possible fallout in international legal and diplomatic forums, from the UN to the European Union to the ICC. A lot of the underlying divide within Israel over the annexation is rooted in the debate about the relevance of those institutions sans American power.

As Lerman quipped, the rules that western European states ask Israel to follow “are in force only in western Europe.” The strategic choices Israel faces are not those of France, Germany or Britain.

In broad terms, this skeptical view holds that the global order is shaped by power, and a happy accident of history – the overwhelming power of the United States in the wake of WWII — imposed a thin veneer of moralizing legalisms on an international system still essentially ruled by hard power. That’s how Americans like to conduct their foreign policy: everything America does in the world must be couched in moral terms.

Yet this moralizing is little more than a story told by the powerful about their power; it doesn’t drive American policymaking. A hint at that fact might be gleaned from the watershed moment in the construction of the modern global order of international law and norms: the Nuremberg trials of leading Nazis in 1946. The trials claimed to set a new moral standard for international conduct — but they could only set them in a military tribunal imposed on a defeated Germany by a triumphant conqueror. It was not law or justice that defeated the Axis, it was carpet bombing and nuclear strikes.

The better world that emerged after World War II, this view argues, is an outgrowth of American power, nothing more. Genocides were stopped not when the world’s conscience was pricked, but when American power swung into action. The safe and open seaways, the stable international financial order – all these global public goods have stood on the necessary foundations of American hard power, and could not have existed without it.

Similarly, the European Union trumpets its “soft” power, but has proven over the past decade it could not influence a Syrian civil war in which it has vital interests and which would drive millions of refugees into its borders. Soft power is a fine thing. Israel desires a role in European scientific research agreements and “Mediterranean dialogue” initiatives as much as any small Mediterranean nation. But it is no replacement for hard power of the sort that could ensure a small nation’s safety as enemies multiply. Western Europe’s talk of its “soft” power sounds to the ears of many Israelis as a way to avoid noticing the fact that Western Europe spent the second half of the 20th century, including the terrifying years of the Cold War, comfortably ensconced behind an enormous and expensive American defense umbrella. Europe was protected by hard power, just not its own.

In the end, a certain type of Israeli defense planner argues, while the niceties of international diplomacy and law should be respected, they cannot be relied upon as a defense strategy. As American power recedes, the idea that one can rely on international norms for safety — that Israel should plan for a better world rather than a worse one — recedes with it.

Dangers multiply

That’s especially true in the Middle East, where the withdrawal of Pax Americana leaves only dangers in its wake.

A Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated regime in Turkey is on the march in Syria and asserting new maritime rights in the eastern Mediterranean. Iran is briefly contained — primarily by America and by the weaknesses of its own regime. But remove America, lift the sanctions reimposed by the Trump White House, and the Shiite axis Tehran has constructed from Lebanon to Yemen is, at least in the short term, contained no more. Russia has moved into the region, as has China with its forward base in Djibouti.

This point is argued by Israeli defense planners on both sides of the annexation debate. The anti-annexationists say a dangerous region and a retreating America require bolstering alliances with conservative Sunni states like Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states. Annexation only makes that more difficult.

But the same vulnerability lends a new importance to the West Bank. A withdrawal from the Jordan Valley, say most Israeli defense planners, now becomes impossible to justify. A vacuum of Israeli security control in the West Bank would be used by rising enemies from Ankara to Tehran — and their proxies and ideological compatriots in Hamas, Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad — to directly threaten the Israeli heartland of the coastal plain.

In other words, an Israeli withdrawal from the Jordan Valley grows more distant as US power recedes. It isn’t Trump’s “window of opportunity” that drives Netanyahu’s thinking, but what some are calling a “window of necessity” forged by a US retreat that began long before the Trump administration. Ironically, a Biden presidency may delay the Israeli effort to lay formal claim to the Jordan Valley — and thus permanent overall security control over the West Bank as a whole — but it won’t weaken it. If Biden continues the trend of the Obama and Trump administrations in seeking to draw down American commitments overseas, he will only strengthen that Israeli resolve.

Jordanian fears

The conservative Israeli view of the world has its answers to the many criticisms leveled at the annexation plan.

It won’t undermine regional alliances, or at least not the ones that matter, says this camp. For the two states most vociferously and publicly opposed to the annexation, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, the alliance with Israel is a “supreme interest,” said Lerman.

“I think [Israeli control over] the Jordan Valley is important to our security, to Palestinian security – and to Jordanian security,” he argued.

That’s not a flippant comment. Since 1970, when Israeli warplanes overflew a Syrian invasion force headed toward Jordan and forced it to retreat, Jordan has in many ways been under de facto Israeli military protection. An Israeli withdrawal from the Jordan Valley leaves a glaring gap in the Jordanian perimeter, a perimeter that already includes long stretches of porous border with splintered Iraq and war-torn Syria. The alliance with Israel isn’t warm, but it doesn’t have to be. Both countries have too much at stake to worry about such niceties. A Jordan desperate for Israel to continue holding and securing its western flank should not be taken too seriously as it postures against Israel declaring that hold, so vital for Jordan itself, permanent.

Putting the car on the road

Annexation offers one final strategic advantage, say proponents.

“In two panels on annexation at [think tanks] JISS and INSS, we reached the same conclusion. The idea of applying Israeli law [in the West Bank] puts the [Trump plan] car on the road,” said Lerman.

That is, it transforms a theoretical plan into an operational one.

“Suddenly we saw the Palestinians wanting to go back to the negotiating table. It made the Trump plan the Israeli centrist plan. It shifted our own politics from opposing poles to a new center.”

The key point, yet again, is a question of power. “Where the Israeli consensus goes, that has resilience,” Lerman believes. If most Europeans imagine one border in the West Bank but most Israelis believe they need a different border, which is more likely to be the final result on the ground?

The Trump plan is vague. Critics, including in Israel, have assailed it from all sides. But it nevertheless provides a number of basic Israeli needs that have become vital truths for most Israelis, including control of the large settlement blocs and of the Jordan Valley.

This domestic political support is another kind of “window of opportunity.” The very existence of such a favorable plan has become a vehicle within the Israeli debate for advancing the sort of delineated defensive border that, its supporters feel, a dangerous new world demands. The debate between the pro- and anti-annexation camp, at least within mainstream Israeli discourse, isn’t about the merits of retaining Israeli control of the Jordan Valley. It is about the timing for doing so.

So why now, when the diplomatic fallout could be so grave?

The answer for Netanyahu and his camp within the Israeli defense community: We do this now because American power is in retreat; because our enemies are on the rise; because our allies won’t really abandon us, since they need us just as much as we need them; and because if we don’t “put the car on the road” – move from theory to practice on a question of existential significance for our future – no one else will.

comments