Historian Helps a Congregation Remember

Ahavath Achim Synagogue tracked down and honored the people who used their Torah before the Holocaust.

The Memorial Scrolls Trust in London knew who to call to ensure Ahavath Achim Synagogue was honoring the history and people connected with a Holocaust-era Torah loaned to AA 40 years ago. Doris Goldstein, a local historian and synagogue member, was known for her centennial history book about AA.

The Torah is part of an exclusive group of 1,800 that were kept in the Jewish Museum of Prague in 1942. They were moved to a ruined synagogue at Michle outside Prague in 1948 until making their way to London in February 1964. MST maintains the database of this Torah collection and allocates them to communities across the world. One ended up at AA and another at Congregation Shearith Israel, which successfully tracked down and honored the people who used the Torah before the Holocaust. AA wanted to do the same.

Jill Rosner, assistant to the AA rabbis, was able to find the names of families from Pilsen in the Czech Republic, which is known for its beer. And on April 7, Goldstein gave a presentation about this Torah, lent to AA in 1977. The Buckhead congregation was then able to say Kaddish.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

“The presence of these scrolls is a reminder of those who were lost – not just the communities, but the individual souls,” Goldstein said. “When people view these Torahs, they should try to remember they represent hundreds of thousands of people who could’ve been making meaningful contributions to the world. What this Torah means to me is what it should mean to everyone – a memorial of those who perished in the Holocaust, and it is our obligation to remember them.”

Jews lived in Pilsen since the 14th century. It is one of the oldest cities in the section of the country known as Bohemia, which developed into an industrial center. By the turn of the 20th century, the community was among the largest and most affluent in the country. A beautiful Moorish-style synagogue had been erected that covered almost an entire city block.

By 1930, Jews made up 2.4 percent of the population, or 2,773 people. But these numbers were augmented by Jews fleeing the western edge of Czechoslovakia, which came under German control in 1938. The following year, Nazis occupied the entire country and the Jews were persecuted and arrested. The Jews of Pilsen were later deported and murdered in concentration camps.

There were more than 350 synagogues in towns in Bohemia and Moravia. Of those, at least 60 were closed and/or destroyed while others were deserted because their members were no longer there. The Jews of Prague designed a plan and persuaded the Nazis to allow them to bring the contents of the synagogues from the now-deserted communities to a Jewish museum in Prague, where the contents were carefully catalogued. There were 212,000 items in the collection, which contained the 1,800 Torah scrolls. The hope was they would be restored to their place of origin after the war. Unfortunately, only 10 percent of those deported survived the war and returned.

After many years, London Jews bought 1,564 of the scrolls from the Communists that controlled the country beginning in 1948. The scrolls were then brought to the Westminster Synagogue in 1964, where some are still housed today. The majority are in synagogues and Jewish institutions all over the world. Some have been restored and are being used, but many are displayed as a memorial to those communities and individuals lost in the Holocaust.

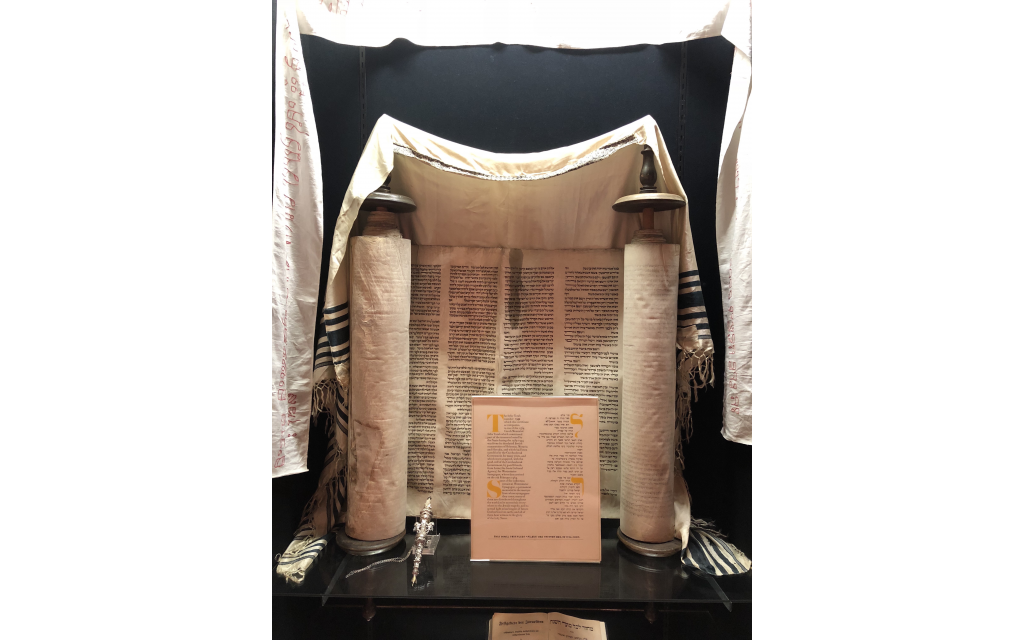

This scroll is #1339 of the 1,800 from Bohemia and Moravia. It is no longer kosher to use in daily worship because of its condition. It is on display in AA’s Sylvia G. Cohen Museum draped in a frayed tallit. It remains a testament to those who lived and died as Jews as well as to those who were responsible for saving it from destruction, Goldstein said.

Compiled with the help of Anne Cohen, Ahavath Achim director of marketing and community relations.

comments