Geffen: Israeli Deaths So Close

Every terrorist killing makes us second-guess aliyah but realize there's nowhere else we could be.

In a new book, “Becoming Israeli,” edited by Akiva Gersh, one of the brief essays states, “I don’t really want to be here but I have to be here.”

For those of us who have lived here 50 years, 40 years, possibly only one year, there is always a similar twitch when the firing, the rioting or the death of a family occurs.

We ask quite seriously: What do I need this for? Why don’t I just go back to my home in the Diaspora?

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The Israel existence concept then racks our brains. How can you live anywhere else? How can you be away from your friends — either they or their children are serving? How can you forsake the poignancy of public mourning for victims struck down in their homes, killed when they took a ride with strangers, blown up when a bomb went off in public, murdered with a knife as they waited at a bus stop?

Yes, we have to be here.

You always remember the first funeral you attend in Israel when the circumstances of the death are not natural. A neighbor, a man in his 40s, was in the heart of Jerusalem. A bomb had been placed in a mailbox; he was killed instantly as he walked by.

Two soldiers were kidnapped along the Lebanese border in the 1980s, never to be seen again alive. Our only soldier then, our oldest son, was sent in with his unit to retrieve the body of an Israeli soldier who had been ambushed and killed while trying to find the kidnapped. Troops including our treasure, our son, crawled through continual fire to bring back the body.

A day later, he returned to our apartment in Jerusalem, and there was a knock at the door. A woman visiting a neighbor a few doors away heard that our son had been in the locale where the unit had reached the body to bring him back. She was the aunt of the deceased.

Our son went with her to where she was visiting and told her the complete story, not skipping a detail. After a half-hour, he returned, drained but having performed a mitzvah.

When a death occurs, every family member — parents, grandparents, all — wants to hear what happened. It is cathartic for the family who has lost one so dear and for the person who has to pour out the story as fully as possible.

Our cousin’s son died in a military action to clean out a nest of potential killers with sufficient arms to cause a major incident in which people, old and young, would be murdered innocently. We attended his funeral; we rode about 50 miles to console the family at shiva.

We attended the funeral of a friend who had been here 45 years.

Her sons’ units released them quickly so they could be at the funeral and could sit the shiva week. At the home, we brought memorabilia about the deceased. We looked at her face, and we cried and laughed at the same time. She was in her 90s, smuggled in as one of the illegals in 1945.

Another cousin died in his late 40s. We mourned with the family — would they ever be the same? We returned to the shiva to help them get through this sad loss of life.

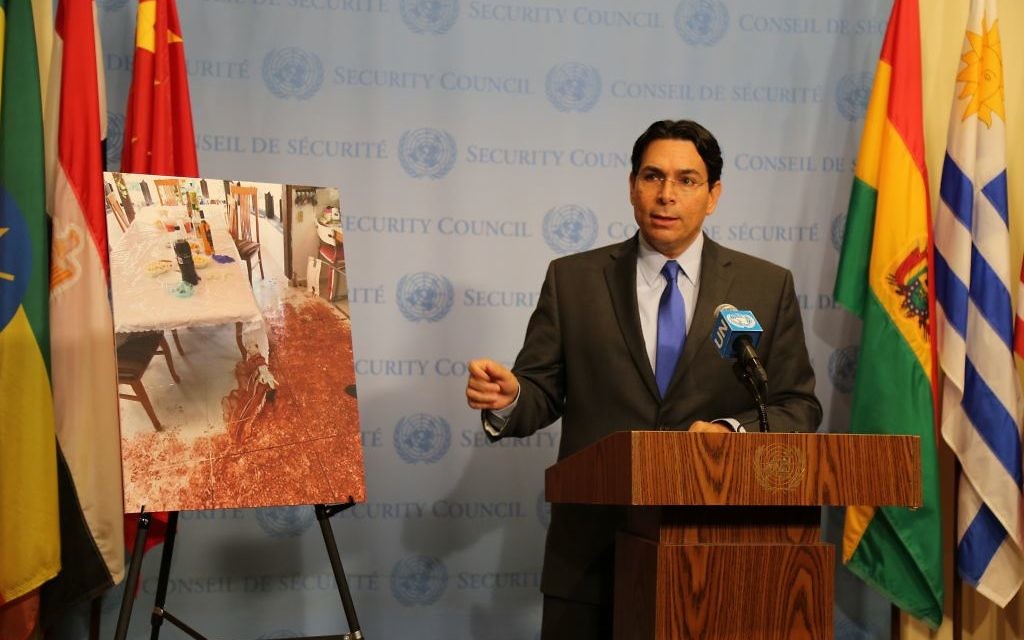

Now almost an entire family is murdered by a terrorist at home. Television shows bloodstains throughout the home. Newspapers have vivid large and small photos of the dead and red-stained pictures as well. We begin to cry.

We don’t attend the funeral, but because we know a friend of a friend of the family, we take a bus to be present during the shiva.

As anonymous as we are, we feel that we must let the survivors know that the wider world of Israelis is with them at this tragic time.

The current incidents at the Temple Mount begin with the shooting of two Druze policemen. They are Israelis but not Jews, yet how deeply they love this country. How close we feel to them.

After closing the Temple Mount so no one can pray at al-Aqsa mosque, Israel sets up metal detectors so those who want to be on the Temple Mount for prayers can legitimately do so. They have been checked.

The steam of the Palestinians begins to blow; hundreds choose to pray at the Lion’s Gate. They can be seen worldwide. The Arab leaders responsible for the holy locale, the Waqf, readily announce that the status quo of the Temple Mount has changed.

The world reacts; numerous countries forget the deaths of the ambushed Druze policemen.

We hear, “Israel has usurped the Arabs’ hold on that holy site.” They even cite the U.N. decision: “The Temple Mount is part of the heritage of the Palestinians.”

Our granddaughter just entered the navy. Her brothers could be called back because they are part of the reserves, having completed their three years of active service.

We feel that Israel is not the place for us, but it is 40 years since we made aliyah.

No matter what happens, this is our home, as it is for so many olim (immigrants). Israel exists; we share its joys, its victories, its trials and tribulations.

Former Atlantan David Geffen, a Conservative rabbi, lives in Jerusalem.

comments