Finding Hope in the Deepest Hell

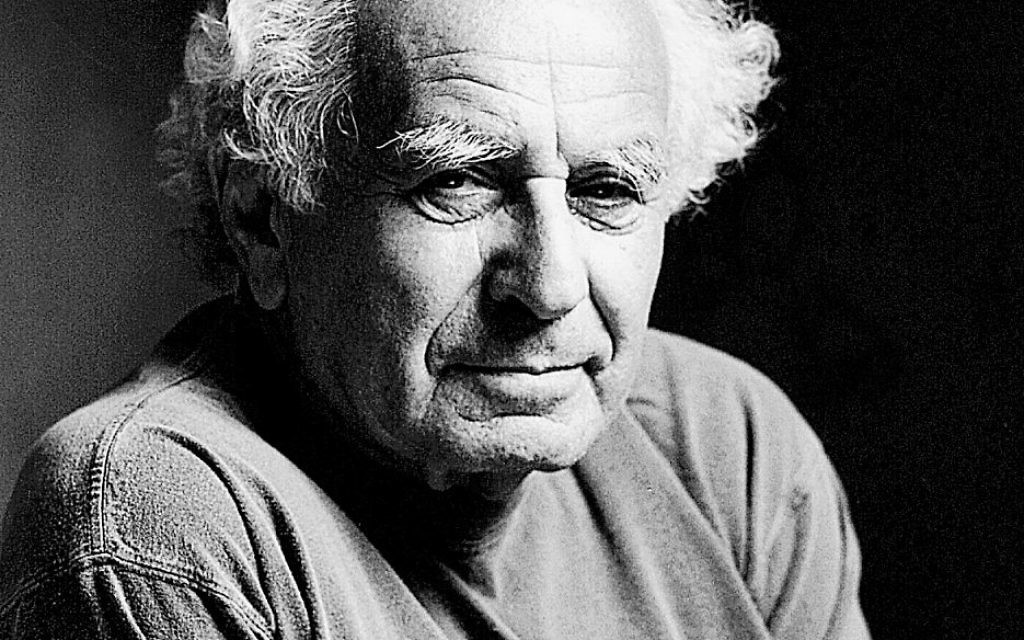

Eugene Schoenfeld relays story of survival in Birkenau.

It was toward the end of April 1944 when the doors of the cattle car slid open, and I and the members of the transport from Munkacs stepped out to face our threatened future.

We formed the lines and walked in front of Mengele. I and remnant members of my male family who were not culled out by Mengele entered the camp’s courtyard and proceeded to run the first of many gantlets. We were sheared like lamb, disinfected with a foul-smelling, dark liquid, and sent into the showers.

It was there, in the showers of Birkenau, that I was introduced to the spirit of the concentration camp.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

We were allowed to keep our shoes, and as we entered the shower room, we placed our shoes in a corner. Unfortunately, when I went to retrieve my shoes, someone inadvertently had taken one of mine. I consulted a kapo, an older inmate whose jacket sleeve bore the designation of a supervisor.

He suggested that I knock at a certain window and request in German a pair shoes, but with a high degree of humility. When the window opened, two people were in the cubicle: an SS guard with his weapon and a kapo, I assumed he was another Jewish inmate, brandishing a highly polished and gnarled stick.

If I remember correctly, I was told to start my request with “Ich bitte geheorsahm,” supposedly meaning “I am humbly requesting.”

I began my request, and the kapo wouldn’t let me finish. He lifted his shillelagh and struck me numerous times over the head.

I walked back to my father crying. I was not crying because the beating hurt me, although of course it did: No one gets his head smashed without hurting. But the frustration, shame and mental pain were stronger than the physical forces and brought the tears to my eyes.

“Father,” this 18-year-old asked his father amid his crumbling world, “how is it possible that today, in the midst of the 20th century, after we reached elevated heights in philosophy, morals and ethics, after all the knowledge we achieved in psychology and psychiatry, after supposedly we had risen in our understanding of theology, we seem not to have advanced from our status of an ape?”

In retrospect, that day when I stood in front of the gates of hell and read the cynical inscription “Arbeit macht Frei” and “Arbeit Macht das Leben Zuss,” if I had been given the opportunity to explore the gate through which I entered the camp or the viaduct under which the train entered Birkenau, surely I would have found Dante’s inscription as well: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”

Indeed, as the poet describes his vision of hell, so it was: a place of eternal pain, a place without justice and G-d, where souls of misery are doomed in an eternal night pierced by no light of stars. A place sans hope.

Or was it?

On rare occasions, I found that the spirit of menschlichkeit existed even among those of us who felt cursed to have our memories erased under the sun. As a gift from heaven, I found that spirit even in a young SS man, who showed me that care, concern and empathy survived among some who were taught to commit themselves to our destruction.

Five miles from Auschwitz was Birkenau, a transient camp. Those who entered it were either gassed and cremated or sent to work camps.

The others included most of my family, their ashes mixed with the soil of the Polish steppes, where they stayed as an eternal declaration of the power of the Freudian id and the consequence of the pandemic of human madness.

We survivors of the initial onslaught of the marauders lived in the confines of the barracks, sitting and sleeping on the wooden-planked, three-tiered beds that six of us called home. Having familiarized ourselves with the work that presumably would make us free, such as emptying and cleaning the slop buckets, we helplessly watched people die from coronary and diabetic diseases that they could have survived for many productive years with the help of medications that they previously took.

Within a week of our arrival, we were ordered to embark once again on the cattle cars — destination Warsaw.

We entered the rail cars and sat down (never permitted to stand in the train) to the right and left of the middle third, the area of the doors and two bunks for the SS guards.

Our guards were quite young. Their smooth skins betrayed their age, no older than 18. The guards were the opposite of each other by their physiognomy and temperament.

One was short, stocky, dark-haired, dark-faced and gloomy, and when he was irritated, which was frequent, he threatened us with his gun. He was Ukrainian.

The other was tall, slender, blond and blue-eyed with an open and smiling face. He had the appearance of a person with an honest disposition, a person to be trusted, with a constant, contented smile. He was a living example of Hitler’s ideal, albeit mythical, Aryan.

His deeds reinforced his image of a trustworthy and kind person. Whenever the Ukrainian threatened us with his gun, the Adonis (for thus was his image) told us not to mind him and placed himself between us and the gun.

But what was most outstanding was what he did.

I often wondered how this young man became a representative of this horrendous Nazi ideology that forced me to be a slave and made him my guardian. But, unlike any other guardian who had domain over me, he cared.

Every time the train stopped on the way to Warsaw, he bolted from the train and later re-entered loaded down with containers of coffee for us. Imagine the effort that he expanded to gather enough containers to do the job.

In the afternoon, when coffee was no longer available at the stations, he brought us water and apologized for not bringing coffee.

I am sure he was real and not merely a wish-induced apparition. And though one forgets the good when badness keeps increasing, he became a reason for my maintaining the belief that goodness and hope exist.

In retrospect, writing this made me realize why we Jews have developed the belief in the continual existence of 36 hidden righteous men who are the maintainers of eternal hope and recognize that the blond SS guard must have been one of those hidden righteous men. For where else do we have such desperate need for hope than in the midst of rampant evil?

comments