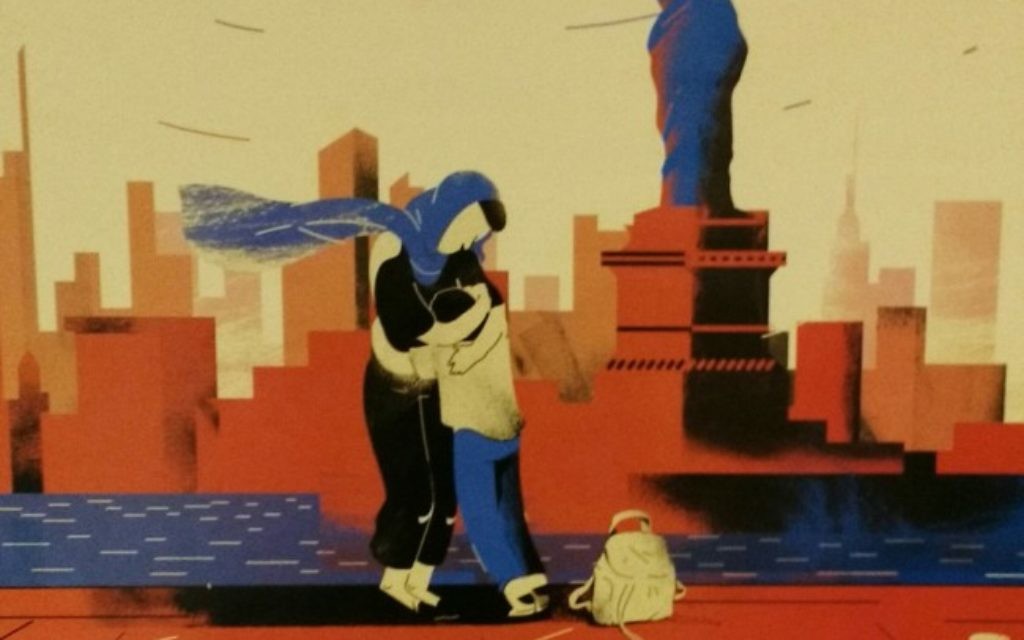

Film Introduces Human Side of Refugee Crisis

Refugee camps “are a short-term solution for a long-term problem,” a U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees official says in the documentary “Salam Neighbor.”

But the average refugee spends roughly 15 years in refugee camps, and only 1 percent of refugees ultimately settle in a new country, JD McCrary, the executive director of the International Rescue Committee’s Atlanta office, told a crowd of about 50 people gathered at Congregation Bet Haverim on Wednesday, July 20, to watch the documentary about Syrian refugees in a camp in Jordan.

While about half of the world’s resettled refugees, generally 70,000 to 80,000 per year, are taken in by the United States, only about 1,800 Syrian refugees entered the country last year, including roughly 75 who came to Georgia.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The Syrians are part of the largest number of refugees globally since World War II, and McCrary reminded the audience that their camps are often neither temporary nor havens.

“Salam Neighbor,” whose planned June screening at Bet Haverim was postponed after the nightclub massacre in Orlando, Fla., and which is available on Netflix, is largely set in the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan — the world’s second largest.

The camp is under UNHCR authority and holds roughly 85,000 people in an area that’s 2½ miles by 1½ miles. The UNHCR provides tents for all families and, with the help of many nongovernmental organizations, supplies basic daily rations for the inhabitants.

Syria’s 5½-year-old civil war has created at least 4.5 million refugees, most of whom have fled to neighboring countries, although many are internally displaced.

“Escaping a war is only the beginning of their story,” the film says at the start.

The film follows two American twentysomethings who attempt to humanize people languishing inside and outside the camp.

Particularly poignant is the story of Raouf, an affable young boy who wants to become a doctor. His father recalls that before the war Raouf was always excited about school, but after the building was bombed by the Syrian regime, the boy became traumatized and refused to continue his studies.

Others featured include Ismail, a university student from Damascus who was studying to be a French teacher and has a flair as a chef; Ghoussoon, a single mother of three who ekes out a living making bows for hijabs 30 minutes from the camp in Mafraq; and Umm Ali, who makes art recycled from trash.

Ghoussoon says that though her children attend Jordanian public schools, they may go only after the Jordanian students finish for the day. In Turkey, by contrast, many Syrians are unable to send their children to public school.

Only half of refugee children receive any sort of education, according to the film.

The young Americans secure credentials to live in the camp for one month, but on their first day they run into trouble when they set up their tent next to one of the camp kitchens — a place where many women congregate — and some of the men voice their concerns.

After coming to an understanding with their neighbors, the Americans are told that they won’t be allowed to stay overnight because Jordanian authorities will not be able to protect them at night from gangs and robbers who might think they have money or other valuables.

Though they are able to film inside the camp for 10 months, the Americans leave each night to sleep in the city of Mafraq. Crucially, the two realize that 80 percent of Syrian refugees in Jordan live outside the refugee camps. Those who remain are unable to leave and work without a Jordanian sponsor, making them beholden to a U.N. agency that is experiencing a worldwide budget shortfall of nearly $3.5 billion just to house Syrian refugees in the region.

The Za’atari camp maintains some semblance of an economy as a small city and even boasts a market dubbed “Champs-Élysées.” Some people are able to piece together ramshackle homes.

But the camp lacks proper sewage and has an overloaded electrical grid, and it is clear that few options are available for people waiting out a civil war that has caused more than 300,000 deaths.

comments