Exhibit Proves Chagall was a Zionist

During Marc Chagall’s time as a painter he rose to become known as a master colorist, depicting biblical scenes in watercolor all over the world.

Patrice Worthy is a contributor at the Atlanta Jewish Times.

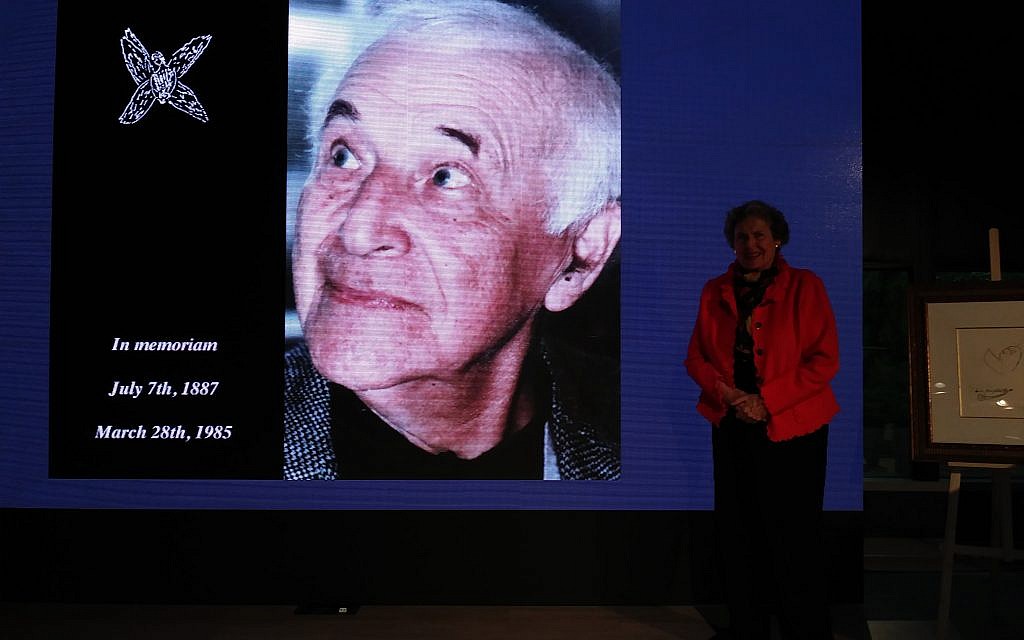

During Marc Chagall’s time as a painter he rose to become known as a master colorist, depicting biblical scenes in watercolor all over the world. Vivian Jacobson, a close friend of Chagall, gave a talk April 14 during the opening reception of “Marc Chagall and The Sacred,” an exhibition at Still Point Art Gallery in Alpharetta.

She explained there is superficial attitude that Chagall was not a Zionist when, in fact, he supported a homeland for the Jewish people.

Jacobson met Chagall in 1974 when he was dedicating one of his pieces in Chicago on behalf of the Hadassah Medical Organization. As their bond deepened, she learned more about the painter, eventually becoming a leading authority on his work as a founding member of American Friends of Chagall’s Biblical Message Museum in Nice, France.

“People don’t say I like Chagall; they say I love Chagall,” Jacobson said before diving into her presentation.

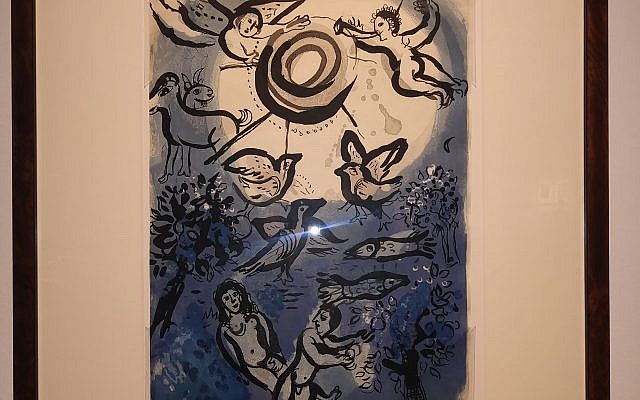

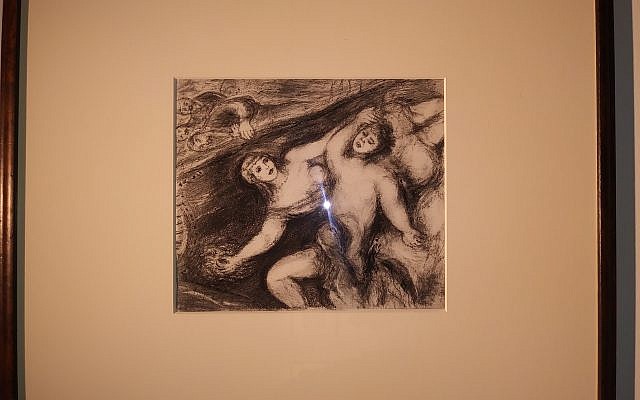

In the exhibition “Chagall and The Sacred” more than 50 lithographs portraying stories from the Torah adorn the gallery space. The exhibit begins with a piece titled “Creation,” and the works tell of the rise, fall and eventual advance of humanity.

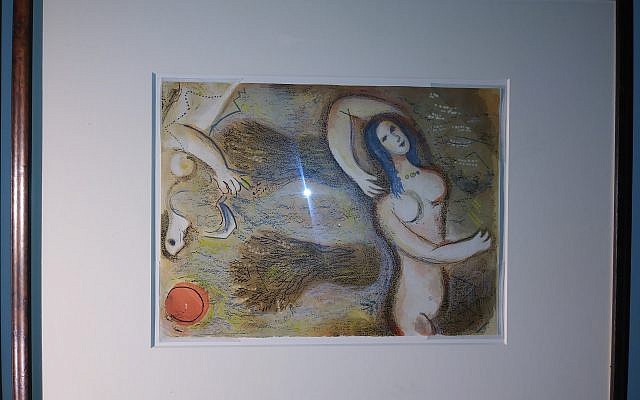

There is the story of Adam and Eve giving in to temptation in the Garden of Eden, then a graphic depiction of the first murder titled “Cain and Abel.” From there moments depicting the continuity of the Messianic bloodline tell the story of the Jewish people from “Tamar, Daughter -in-law of Judah,” “Moses I,” “Moses II” and “Naomi and Her Daughters-in-Law,” a painting that puts Naomi in the middle of Ruth, the first Jewish convert, and Orpah. The three are enclosed in a hug that radiates the warmth and love of a story about family, loyalty and hope.

Then there is “Ruth at The Feet of Boaz,” followed by the story of David told through four paintings: “David Saved by Michal,” “David and Absalom,” “David and Bathsheba,” and “David with a Harp.” David is painted in multiple colors with red as the dominant hue to convey his passion and complex character. David is not perfect, but his passion and determination made him one of the greatest leaders in the Torah.

Chagall used color to give depth to his pieces and, like the Torah, they are layered in meaning. His first layer is sketched with a pencil, giving a simple structure to the piece; then it becomes more nuanced with color.

“Abraham is painted in many different colors because he is the father of many nations; if he was painted one color, he would just be the father of one nation,” Jacobson said quoting a child.

The watercolors are translucent, allowing viewers to see each layer with clarity, a characteristic of the Torah and its text.

Chagall was born on July 7, 1887, and grew up in an Orthodox home where he wasn’t allowed to paint because of the commandment: Thou shall not make any graven images. So as a young boy he found inspiration in an unexpected place, Jacobson said.

“He would go to church behind his house and see beauty and color he couldn’t in his own home synagogue,” Jacobson said.

His mother finagled him into an art school that traditionally banned Jews. After that, Chagall spent the rest of his life painting, Jacobson said.

He was a firm believer in Zion and, having lived through the pogroms and two world wars, he supported a homeland for Jews. As his reputation grew, Jacobson said he waited for Israel to commission him for a piece.

“They were busy building a country and had their mind on other things,” Jacobson said. “The Jews did not have money to get stained glass windows; meanwhile he was doing them in France.”

Finally, in 1960, he was commissioned by The Hadassah Foundation to create stained glass windows for the Abbell Synagogue at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem.

“His genius was in his stained glass,” Jacobson said.

Each window depicts one of the blessings Jacob gave to his 12 sons who became the 12 tribes of Israel. He went on to create three large-scale paintings for the Knesset depicting the story of Israel and its people. Chagall created all the works of art in the Knesset, including the 12 floor mosaics.

“He was there to unveil the Hadassah hospital windows and saw the large empty walls of the Knesset and was inspired,” Jacobson said.

The three tapestries in Chagall State Hall were commissioned in 1965 and completed in 1969. The first tapestry portrays Jacob’s dream, the revelation on Mount Sinai and the sacrifice of Isaac. The second depicts various events from Israel, including Moses receiving the law, the exodus from Egypt, a burning village symbolizing the Holocaust and David playing the harp. The last tapestry portrays a return to Zion, including Ruth, Boaz and David as central figures.

Jacobson said Chagall, who painted well into his 90s, used his talent for tikkun olam or to repair the world. He expressed his love of the Bible and how he felt about the Jewish people and Jacobson said it is evident in his work.

“Chagall was not a practicing Jew, but he believed in a homeland for the Jewish people,” Jacobson said. “He demonstrated his love of the Jewish people through his artwork.”

comments