Cuban Jewish Memories Then and Now

Ruth Behar, delivering the Tenenbaum Lecture at Emory University on Feb. 13, officially became a genius in 1989.

Ruth Behar, delivering the Tenenbaum Lecture at Emory University Feb. 13, officially became a genius in 1989. At the age of 32, she won a MacArthur Fellowship. They are the so-called “genius” grants made each year by the John and Catherine MacArthur Foundation.

The daughter of Cuban Jewish immigrants who came to this country after the Castro revolution, she was the first Latina, and up to that point, the youngest person ever to receive the coveted award.

Today she is a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan and a renowned authority on the Jews of Cuba.

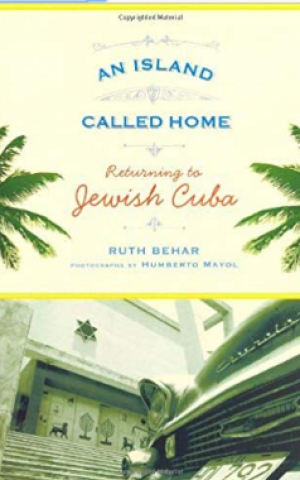

Among her books is “An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba” and a documentary she created, “Adio Kerida: Goodbye Dear Love,” about her rediscovery of the country of her birth, which she left when she was five.

Her Tenenbaum lecture is entitled, “The Jews of Cuba and their Diasporas: Memories, Stories, Dilemmas.”

We spoke recently about the meaning of memory for those Jews who emigrated from Cuba so many years ago.

Behar: I’m really referring to both inherited memories and the memories that I’ve heard from others who left when they were older. Many people haven’t gone back, including my own parents. They have all these memories there. Cuba is really constructed through memory so that that’s the sense in which I want to address memory. Memory is so important because it’s what kept Cubans connected to the island even if they’ve never gone back.

My mother actually brought with her my school uniform from the Jewish school in Havana that I briefly attended when I was 4 years old. It had a little Jewish star embroidered on it. And she brought her honeymoon night gown made with the lace that her parents sold in their store in Havana.

And all of the Cuban women when they left, Jewish or not Jewish, would take the family photo albums. So all of these black and white photographs were crucial to me — family gatherings on the beach, weddings, just all those life-cycle events. Those pictures were absolutely essential, and the photographs, kind of like the memories we had, became a sort of substitute for that lost Cuba.

AJT: And how well was Jewish life woven into these memories?

Behar: Well, Jewish life was woven in a very interesting, hybrid way. There was no contradiction for my family, and I think for most Cuban Jewish families, between being Jewish and being Cuban. Even after we came to America, I grew up going to bar mitzvahs where we would dance to Cuban music and the bar mitzvahs that would take place in Miami, they would have Cuban or Latin bands playing. And we always would form a conga line.

Like at the end of the party, you know, when we’d all dance the hora, there would be a conga line, you know, just like in Cuba where people dance the conga.

It’s like there are interwoven identities. And that’s how it was to the Cuban Jews. Like everything that was part of Cuban culture was part of Jewish culture for Cuban Jews.

I think most of the time it was very fluid. But the one thing that’s important to note is that, in at least one respect, Jewish Cubans tried to maintain an insular community, a kind of an island within the island, because they didn’t want their kids marrying out. The pressure was to marry within the Jewish tribe and those who didn’t really were kind of expelled from the Jewish community.

AJT: Even though the Jewish community in Cuba is very tiny today, there seems to be considerable interest in it these days. There are trips by Jewish community groups, including trips that have been made from here in Atlanta. Why do you think so?

Behar: I’ve thought a lot about it. Cuba continues to play a central role in the American imagination, in part because of its history before the revolution in 1959, where it was a very important place for American visitors to go and let loose.

But there’s a certain aura in the imagination after 1959. Whatever you may think of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara they were very sexy kinds of revolutionary figures, larger than life mythical guerrilla heroes, and so there’s a fascination with that.

I think the other part of this is the Jewish part. In a sense it’s a miracle that Jewish life has survived in Cuba under communism. Some people know that there’s a kosher butcher shop in Havana that has never shut down since the revolution. Fidel Castro personally made sure that it continued. There’s something special about Jews in Cuba that is more vibrant, more committed, and more persistent in their Jewishness.

Ruth Behar’s Tenenbaum Lecture will be presented by Emory’s Tam Institute for Jewish Studies, 7:30 p.m. Feb. 13 in Ackerman Hall at the Michael C. Carlos Museum. The event is free.

comments