Courts Lag Years Behind Tech’s Assault on Privacy

Privacy is a broad topic, and many of the complexities that have arisen around the issue are only now being decided by the courts. So how do we define “The Right to Privacy in an Age Where There Is No Privacy”?

On Dec. 9, addressing that question in the third segment of Congregation Shearith Israel’s Scholars and Authors Series, lawyer Don Samuel noted that the term “privacy” doesn’t appear in the Constitution, but scores of Supreme Court decisions, including some written by conservative Justices Antonin Scalia, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, rely on the right to privacy.

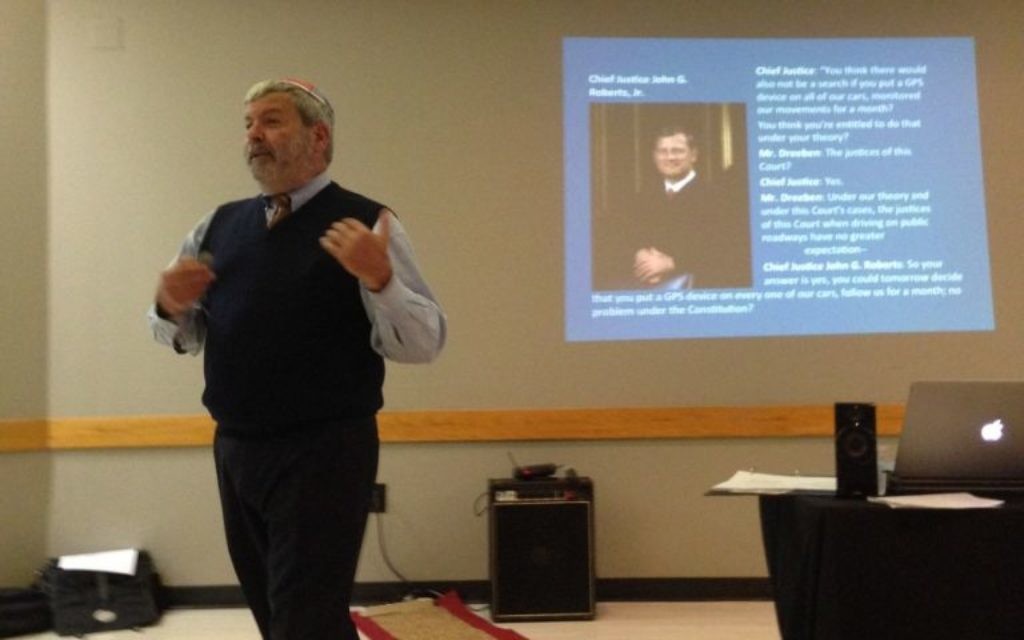

Don Samuel talks about the Supreme Court’s pro-privacy-rights ruling in the case of the United States vs. Jones.

The roots of privacy have been derived over time, Samuel suggested, from:

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

- The Third Amendment’s right not to have soldiers quartered in your home.

- The Fourth Amendment’s right to insist that police have warrants before they conduct any search and seizure.

- The First Amendment’s rights of association and of practice of religion.

All are considered to be part of the right to privacy.

Therefore, one of the rights we consider to be basic and inalienable has evolved through years of adjudication and interpretation, Samuel said, but given the speed at which technology is developing, the courts have fallen far behind society.

Samuel said one concept of privacy “is that there are certain things that we insist that we have, that we own ourselves and are not to be taken by other people” (or the government or companies), such as the rights not to have other people acquire information about us, not to be physically surveilled, not to have our private information shared, not to have our phone calls recorded or intercepted, and not to have our mail and email read, as well as the rights to be left alone, to associate with people of our own choosing, to use contraception and to get an abortion.

The Supreme Court protects all of those rights to privacy.

Secrecy and privacy are related, Samuel said. “The right to privacy can be considered in terms of information not being acquired from you (secrecy), and the second part of the right is not to have the information that you give or is acquired lawfully shared (privacy).”

Every day we give out information about ourselves with the expectation, the right, that it will not be shared. We file tax returns with the civil division of the Internal Revenue Service and have the right not to have those returns shared with the criminal division. We sign Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act forms outlining our health privacy rights. Social Security information may not be shared. Grand jury investigations are private.

In light of all that is restricted, what information can be taken by the government or by companies without our consent? The courts are struggling with those cases.

The Fourth Amendment raises the issue of defining reasonable and unreasonable searches and seizures and probable cause for warrants, and Samuel said court decisions ultimately are based on what the community expects and what our society will tolerate “when it comes to the government interfering in our private lives.”

Samuel describes United States vs. Jones, a case he has before the Supreme Court. His client, a suspected drug dealer, was initially tailed by law enforcement without a warrant. When that surveillance yielded nothing, a GPS device was mounted under his car.

The first court-decided question regarding Antoine Jones’ right to privacy is that there is no expectation of privacy while you drive on public roads. Drivers can be seen by other people, by law enforcement and by surveillance cameras.

But Jones was surveilled 24/7 through the GPS device — new consumer technology in 2004 — resulting in over 2,000 pages of data across 28 days. Is that kind of search legal, or is it a search at all? Is it reasonable?

Pivotal was a case from the 1970s. In Smith vs. Maryland it was determined not to be an invasion of privacy for the government and law enforcement to keep track of the phone numbers you call and the numbers that call you because you give that information to the phone company. If you initially share information, there is no expectation of privacy.

Scalia applied that thinking to Jones, saying, “If there is no invasion of privacy for one day, there’s no invasion of privacy for a hundred days.”

Justice Elena Kagan confirmed the point by referencing surveillance cameras and saying there is no expectation of privacy in public places.

Chief Justice John Roberts, however, found issue with the fact that the “search” was initiated without the permission of a judge and with no restrictions ever. The argument expanded to the slippery slope of allowing the monitoring of the public movement of any citizen, at any time, for any length of time — which would include the judges themselves. Technology now makes that possible.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked what would happen to the huge amount of data collected on everyone. How would the use of the data be restricted?

The Supreme Court had to decide what to do when a proven drug dealer claimed the right to privacy, a right not expressed in the Constitution, in a case involving new technology. Samuel said the argument focused on violating a criminal’s Fourth Amendment rights and ensuring “that the government makes limited use of whatever information they are acquiring about us.”

In the end, all nine Supreme Court justices ruled in favor of Jones’ right to privacy, saying that putting a GPS device on the drug dealer’s car was a violation.

“It was a monumentally important decision when it comes to the right to privacy,” Samuel said.

He then detailed the amount of data available through cellphone records, including the thousands of requests per day for this information made by law enforcement. Customers have given all of the information to the cellphone companies, so they have no expectation of privacy.

The Supreme Court has not taken up a case on that data collection. But in 2011 law enforcement made 1.3 million requests for caller location, and every court approved the use of these cellphone records. The implications are huge because the United States now has more cellphones than people, Samuel said.

He said cases typically take six or seven years to reach the Supreme Court, which thus is continually writing decisions on technology that existed eight years ago. The justices just can’t keep up. Volumes of decisions on the right to privacy, though they will be late in coming, have yet to be written.

Samuel said each person must decide how much personal information he or she is willing to share, but, by owning cellphones, we have abdicated many of our privacy rights. The question that remains is how much information we as a people are willing to let the government take from service providers to conduct investigations of any sort.

—

Samuel’s Case File

A 1980 graduate of the University of Georgia School of Law, Don Samuel has spent most of his career practicing criminal defense law at the firm now called Garland, Samuel & Loeb, P.C.

He has appeared in federal courts in 21 states, has spoken at several conferences and seminars across the country, and has published a formidable list of law review articles and an online compilation of federal cases favorable to the defense that now exceeds 1,700 pages and 6,000 cases.

Samuel has been listed in “Best Lawyers in America” every year since 1993, and in 2014 he was named the State of Georgia Lawyer of the Year in the field of criminal law. He also received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers in 2014.

His high-profile cases include serving as co-defense counsel in the Atlanta double murder trial of Baltimore Ravens linebacker Ray Lewis and as counsel for Ravens running back Jamal Lewis in 2004. He was co-counsel in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Georgia vs. Randolph, in which the high court ruled in 2006 that a consent search of a residence is not permitted if one spouse objects. He was also counsel for the chief financial officer in the infamous Gold Club trial.

Samuel is an adjunct professor of law at Georgia State University and this year will teach a course at the University of Georgia School of Law alongside Larry Thompson, a former U.S. deputy attorney general.

comments