Contact Tracing COVID-19

Following the pandemic’s path is not a simple task, yet it is a crucial tool in controlling the virus’s spread, according to an Atlanta contact tracer.

Chana Shapiro is an educator, writer, editor and illustrator whose work has appeared in journals, newspapers and magazines. She is a regular contributor to the AJT.

Leanna Ehrlich came to Emory University to get a Master of Public Health degree in the global health department. Her focus was on chronic disease related to diet and physical activity, and she planned to complete summer requirements for the degree in her field. Ehrlich had worked in other public health venues, which included a year in Nicaragua for Global Brigades, a nonprofit health and sustainable development organization, followed by four years at a Boston public health research and consulting company, all focusing on chronic disease. “I had very little interest or experience in infectious disease,” she noted.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, it was almost impossible to leave to work in global health, yet opportunities opened in the fight against the pandemic here. “That’s how I got involved in contact tracing,” Ehrlich explained, “and I’m glad I did!”

Contact tracing is the process of reaching people who tested positive for COVID-19 and asking them to identify others with whom they have had close contact. COVID-19 is categorized as a “notifiable disease,” meaning that the results of all COVID-19 tests in each state are reported to the state’s Department of Public Health. From there, the results are filtered to separate counties, and contact tracers follow up by reaching those who tested positive for the virus and locating people who have been in contact with them.

Those who have tested positive don’t always receive notification in a timely manner. A tracer can speed up the process by being the first person to tell someone their coronavirus test was positive. If they have no symptoms, they may be surprised. Ideally, they agree to self-isolate for the required period of time during which they might infect others.

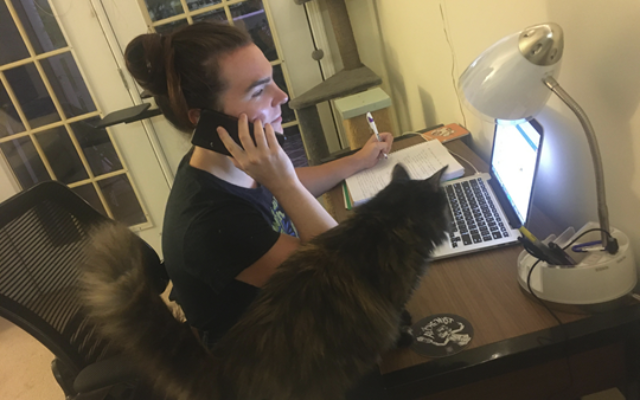

Ehrlich works two or three shifts of three to five hours weekly. There are two different online portals in which she enters information. The first, case interviews, is for people who have tested positive. The second is contacts, for people who have been in close contact with those who tested positive. Each interview is over the phone, and all information is entered in secure and HIPAA-compliant (health information privacy) portals. The tracer’s task is to get information and a list of symptoms that both groups of people are experiencing.

The job is not always easy. “I’ve received a whole range of responses,” Ehrlich said. “First, it can be hard to get folks on the phone. I often play phone tag and might never make contact. Once on the phone, people react in a wide range of ways, depending on their personality. When we get in touch with a contact, people are understandably worried, especially when we are the first to deliver this news.

Fortunately, because COVID-19 has been in the media for so long, most people know the drill. Most important, we always give cases and contacts an opportunity to ask us any questions they have, make sure they have the ability to safely isolate or quarantine themselves, and clarify which symptoms warrant going to a hospital versus recovering at home.” All interviewees are sent helpful follow-up information, she said.

Tracers collect as much data as possible, helping epidemiologists discover why some demographics may have worse symptoms than others. Tracers ask a long list of personal questions, including living and work conditions, age, gender, ethnicity, underlying medical conditions and travel. There is no requirement that they answer.

Responsibilities include correctly entering all information in the secure online portals. Other tracers work at the local, state and national levels to aggregate data about who is affected and where they are located. For example, knowing where someone who tested positive goes to school can help epidemiologists look for an outbreak there.

Summing up her experience, Ehrlich said, “This summer has been a completely unexpected, rewarding learning experience, definitely not what I thought one of my summer jobs would be in grad school, or ever. I have learned a lot, hopefully helped contain the coronavirus pandemic in Fulton County, and had a memorable professional public health experience I will never forget.”

Note: Ehrlich’s observations are personal and do not reflect the official position of the Fulton County Department of Health.

comments