The Case for a Smaller Exodus

The Exodus happened, but probably not with 2 million ex-slaves wandering around the Sinai for 40 years.

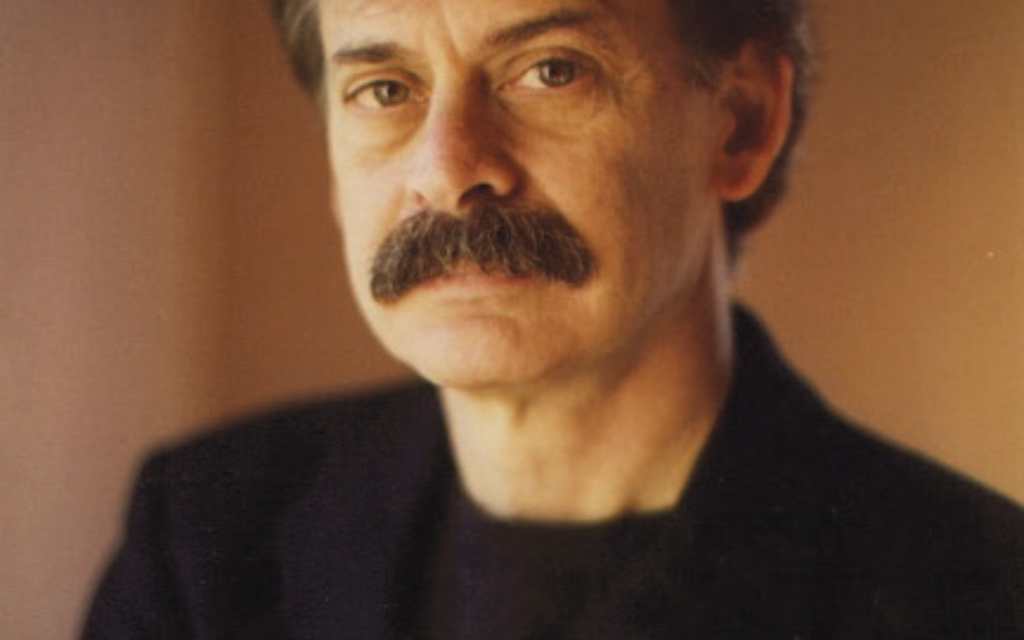

Richard Elliott Friedman, the University of Georgia’s Ann and Jay Davis professor of Jewish studies, made the case for a smaller but still crucial Exodus during a post-service speech Friday night, April 15, at Congregation Shearith Israel.

If you believe every word of the Torah is literal truth dictated by G-d at Mount Sinai, you probably shouldn’t waste your time with this column. But if you’re willing to entertain scholarly theories that the Torah is a compilation of the work of several writers working over several centuries (which doesn’t rule out divine guidance), Friedman’s ideas offer an exciting possibility for how we came to be the Jewish people. (Warning: Because this presentation happened during Shabbat, I didn’t take notes or record it, so I wrote it 24 hours later from memory. Anything that sounds crazy or just wrong is undoubtedly because of an error on my part in conveying Friedman’s thoughts.)

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The professor rejects archaeologically based claims that the Exodus never happened.

He acknowledges that 2 million Israelites (an estimate based on the Torah’s report of more than 600,000 men leaving Egypt) would have left an immense amount of human waste, as well as other archaeological evidence, through 40 years of wandering. So many people also would have stretched across a significant portion of the desert.

But that lack of artifacts doesn’t prove the Exodus never happened. The desert is good at hiding things; Friedman noted that an Israeli jeep lost in the Sinai in 1973 was found 50 feet under the sand a few years ago. And contrary to anti-Exodus claims, he said, the Sinai has not been subject to thorough excavation; it has been surveyed by jeep and excavated at a few select spots.

The lack of archaeological finds does argue against the numbers we hear in the Exodus story, but the evidence of a smaller Exodus could lie hidden in the desert. That smaller movement of people fits the archaeology in Egypt, where there is strong evidence for Semitic foreigners living for about 400 years, and works with the archaeology in Israel, which lacks evidence of a great conquest in the 13th century B.C.E, but does have extensive signs of Israelite occupation before that period.

The theory the author of “Who Wrote the Bible?” presented at Shearith Israel uses the evidence of the Torah text to fill in the blanks of the archaeological record.

In short: Most of our ancestors never went down to Egypt and instead lived continuously in Israel from the time they arrived, quite possibly, as Abraham’s story tells us, from Mesopotamia. The people who dwelled in Egypt, escaped and returned to the Promised Land were the Levites. They were welcomed as kinsmen and, in part because of the lack of available land, were made the priests and teachers.

Over time, as those Levite teachers taught their own story to everyone, all of the tribes accepted it as their history. The conquest story and the exaggerated numbers developed as a result.

The textual support for the theory includes:

- The two oldest parts of the Bible are the Song of Miriam and the Song of Deborah. The Song of Miriam doesn’t say anything about 600,000 men, and the Song of Deborah doesn’t mention Levi in recounting the tribes Deborah rallied for war.

- The ancient meaning of Levite was an attached person — an outsider who joins those already here. Regardless of their ancestor, the people who arrived from Egypt would have collectively been known as Levites because that’s who they were in Egypt and Israel — an alien group joining the others but remaining apart.

- Every person in the Torah with a recognizably Egyptian name was a Levite.

- The portions of the Torah that provided the details of life in Egypt, emphasized fair treatment for slaves and strangers, and drove home the importance of retelling the Exodus story as if every generation had been redeemed were recorded by Levites.

Those new arrivals from Egypt brought crucial elements to pull together the Israelite religion into Judaism, including the four-letter name of G-d, which was unknown to the patriarchs, and those commandments the Egyptian-named Moses brought down from Mount Sinai.

Just a little something extra to talk about at your seders.

comments