Camp Coleman: Centuries of Meaning in Random Encounters

A 500-year-old relic reaffirms religious ties between the past and present.

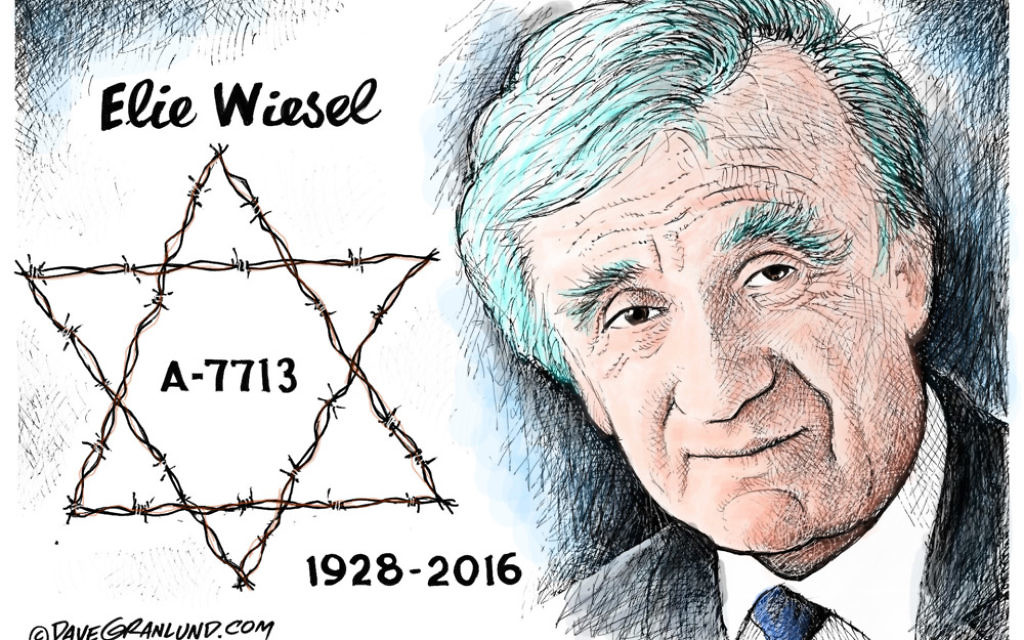

On Friday nights at camp I always share a story with our Camp Coleman community. One of my favorites is a story that Elie Wiesel told our class at Boston University one day more than 30 years ago about an encounter he had in Saragossa, Spain, when he was a correspondent for the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth.

In a cafe, a man approached him and offered to be his tour guide for free. As they spoke, it soon came out that Wiesel was Jewish and knew how to speak Hebrew. The tour guide said, “I’ve never met a Jew or someone who understood Hebrew, but I have something I want to show you, and you can tell me what it is.”

The two men walked to the guide’s villa, and when they entered, Wiesel noticed a large picture of the Virgin Mary hanging on the wall. Asking Wiesel to wait in the main room, the tour guide stepped into an adjacent room and returned with a fragment of a yellowed parchment and asked Wiesel if it was Hebrew. It was.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Wiesel took the parchment, and as he read it, his eyes widened in awe of what he was reading.

He realized he was reading a document that was nearly 500 years old. He started to translate it for the guide. This is what it said:

“I, Moshe Ben Avraham (Moses, the son of Abraham), forced to break all ties with my people and my faith, leave these lines to the children of my children and theirs, in order that on the day when Israel will be able to walk again, its head held high under the sun without fear and without remorse, they will know where their roots lie. Written at Saragossa, the ninth day of the month of Av, in the year of punishment and exile.”

Wiesel exclaimed: “This is an amazing historical document. We must share it with scholars, museums.”

The guide pulled it closer to his chest and said: “I am forbidden to let this out of our family. It has been passed down to me as it was passed down to my parents. They told us that if it was lost, a curse would come upon the entire family.”

Wiesel then understood that the guide was a direct descendant of Moshe Ben Avraham’s.

In awe of this discovery, the guide asked Wiesel to describe how he was connected to Moshe Ben Abraham. Wiesel described the Jewish history of Spain. He explained that after centuries of persecution and torture, Spanish Jews were forced either to convert or to leave Spain or to face death.

On Tisha B’Av (the ninth day of the Hebrew month of Av) in 1492, the day referenced in the document, all Jews were officially expelled from Spain. The guide’s ancestor had been forced to convert to avoid expulsion and wrote this letter to his children so that the truth of their origins would not be lost.

The guide was overwhelmed, and before they said their goodbyes, he asked Wiesel to write down the translation of the document

Five years after this encounter, Wiesel was on his way to cover a story at the Knesset in Jerusalem when a man stopped him on the street. The man said in Hebrew, “Hello! Don’t you remember me?”

Wiesel did not recognize him. The man then said, “Saragossa, Saragossa,” and suddenly it clicked.

The guide said, “I have something to show you.”

He took Wiesel to his apartment. He opened the door and showed him a picture frame with the yellowed parchment hanging on the wall. But this time the man read it to Wiesel: “I, Moshe Ben Avraham, forced to break all ties …”

The two men spoke for a while, and the guide shared that, after their meeting in Saragossa, he had pursued learning Hebrew and eventually decided to move to Israel. As their second meaningful encounter was about to end and Wiesel got up to leave, the man stopped him and said: “You forgot to ask me my name. I want you to know my name. It is Moshe Ben Avraham, Moses, son of Abraham.”

I am not even sure that I can describe all or even most of the reasons that this story resonates so deeply for me. Perhaps it is a story of loss and revival so relevant to our Jewish story.

I also love that what seems like such an ordinary and random encounter between Wiesel and the Spaniard ends up as a life-changing one filled with deep significance and meaning. Or is it that the story captures so well how small actions like taking a few extra moments to write a note to one’s children can make a difference even 500 years from now?

When I share this story, I carry with me a mockup of what that parchment might have looked like. I tell the community that it is not an authentic replica but something that was made in our camp art room.

I include this parchment because I want them to believe that the story can be real — that our actions really do matter, that our encounters and relationships and how we treat each other, even the random stranger, mean something today about the people we are trying to become both individually and collectively.

Bobby Harris is the director of URJ Camp Coleman (campcoleman.org) and the director of youth and camping services for the Union for Reform Judaism’s Southeast Region. The Elie Wiesel story appears in Wiesel’s book “Legends of Our Time.”

comments