America’s Soulless Approach to Medicine

Do we wish to be known as soulless America, just as Phenix City was the soulless city?

In 1965 I moved to Memphis, where I was told with great pride that the city had more churches than gas stations. There is a great pride among the population of the United States that this country is religious — almost as religious as India.

The National Opinion Research Center’s data consistently show that most people in the United States believe in G-d’s existence and that 85 percent of the population believes in life after death. But do those findings mean that the population of this country is religious?

The answer depends on how one defines religion.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

If we define religion by a belief in a deity and church attendance, the United States wins, hands down. But if we define religion by a belief in a moral society and care and concern for people’s need to have a high quality of life, I am not so sure.

I remember well the complaint of one person that his minister had four rotating sermon topics: smoking, drinking, sex and gambling.

During the Vietnam War, I conducted a study (initiated by the ministers association of German Town, a suburb of Memphis) regarding appropriate sermon topics. Church members, responding to the questionnaire, vehemently opposed the idea that ministers should challenge the moral validity of that war.

The responses reminded me of a movie about “Sin City” — Phenix City, Ala., where the city was ruled by heartless, corrupt criminals. The members of the local crime organization, on the one hand, complained that the minister in his Sunday sermon didn’t adequately emphasize fire and brimstone and, on the other hand, immediately after church services ordered the execution of people who opposed the corruption of city leaders.

Perhaps this problem had its roots in the Christian teaching of the duality of power, in which G-d and Caesar have separate domains. Heaven and earth are separate, and G-d’s just domain ends when it comes to governing on earth.

Perhaps this lack of concern with this world and the people in it was brought on by Christian rejection of the Jewish Bible, including the rejection of the moral ideals of the prophets. The Torah and the prophets place moral life ahead of faith and hence espouse the view that obedience to G-d does not end with a declaration of faith but includes morals.

From that perspective, economic institutions are not free from moral laws, and business is not governed only by the law of self-interest and profit.

Sociologist Max Weber, at the end of his treatise of the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, bemoans that capitalism in the United States rejected its Protestant moral and ethical roots in favor of the profit motive.

“Get all you can get” is the dominant approach without consideration of collective needs and interests, which are subsumed under the false concept of rugged individualism.

What is more moral, the saving of human life or the right to private property? Is it moral if we make medicine available only to those who can pay for it and let the others die?

The precipitous rise in the cost of medical care in the United States, including the prices for even generic drugs, seems to support the beliefs that property rights are more important than human life and that human value is judged by wealth alone.

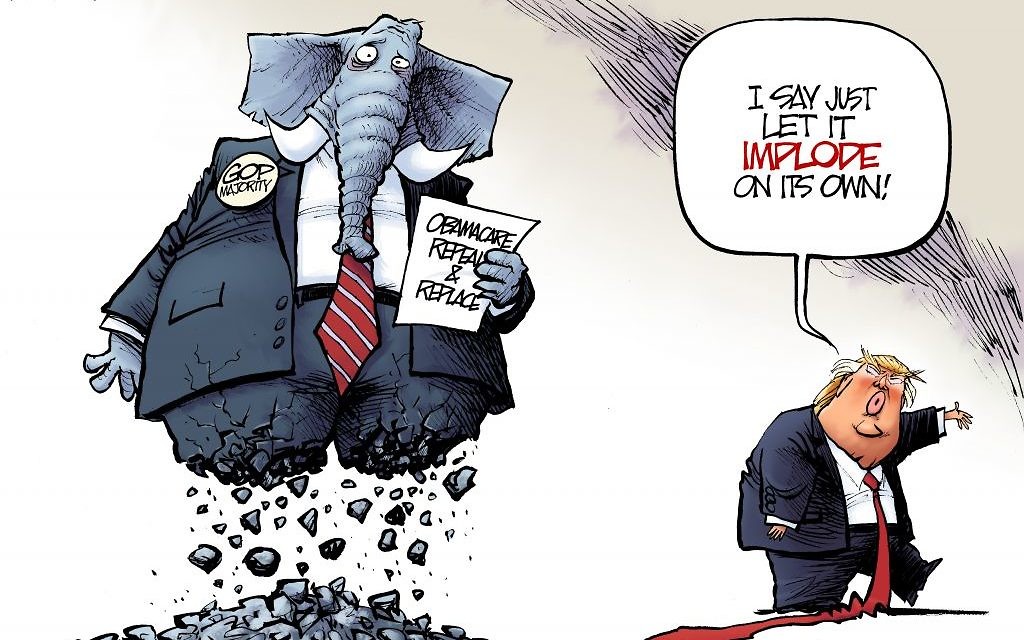

The opponents of Obamacare bring this perspective to justify their view of the value of human beings.

Jews, at least those who have followed the moral dicta of the Torah and the prophets, have always distinguished between private and collective needs (tzorchey yachid and tzorchey tzibur). For many years we sought G-d’s blessing on those who were concerned with collective needs and who understood that all human life had an equal intrinsic value, so that saving one life was equivalent to saving all mankind.

Is there a great difference between those teens who stood by and mocked a drowning person rather than extend help and those people who do not want to provide for the collective needs of health — not as a matter of charity, but as a right for all people, poor and wealthy alike?

The United States is the only industrial country where the real right to life is not granted, yet we wish to call ourselves the richest country. Rich in production, perhaps, but are we also the poorest country in moral belief?

Perhaps it is time to realize that the bare-knuckle capitalism of the 1920s and 1930s is gone, and the new economic system accepts the moral teaching that there are areas of life in which the profit motive is without merit.

Perhaps all those good people in Congress should remember what the Gospels of Mark and Matthew taught about gaining the whole world and losing one’s soul. Do we wish to be known as soulless America, just as Phenix City was the soulless city?

comments