Against Nazis, Failure Wasn’t an Option

By Cole Seidner

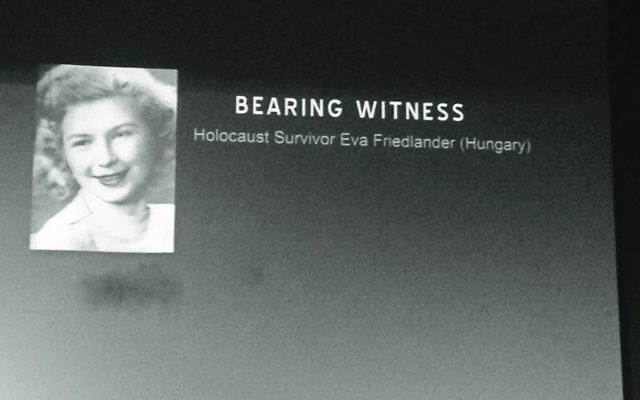

Eva Friedlander was happy as a young child in Budapest. She was well-educated, learning English and German at a young age. She made friends with other children at the park.

But the rise of the Nazis in Germany put pressure on other countries in Europe, and soon she had experiences with anti-Semitism as well. Something as simple as inviting a friend from the park to play at her home was put to a halt.

“Her mother told my mother that she cannot come,” Friedlander said during a Bearing Witness program at the Breman Museum on Sunday, Nov. 8. “And this was repeatedly happening, and finally my mother admitted to me that the reason she cannot come was her mother did not want her daughter associated with Jewish children.”

Later, as Nazism took over during World War II, things got worse in Hungary. New laws were introduced, including the infamous yellow star.

“There were many instances in grocery stores or in public places where they snickered at me,” Friedlander said.

Her education stopped at age 14. Her father lost his work and soon left his wife and daughter. Without his income, young Eva had to find work herself. The war made that search difficult, and she often floated from job to job, calling herself Barbara to avoid suspicion.

In effect, Friedlander was hiding in plain sight as she managed to go from job to job and from one side of Budapest to another. She met her mother every three to four days and kept in touch, but every day was a struggle for food and for shelter.

“I told myself, ‘Failure is not an option. I must do this,’ ” Friedlander said.

And she did, surviving the war to open her own store afterward. With her work experience as a secretary, she was able to notarize documents and help translate papers.

“In a couple of days, we quickly improvised a business,” she said, proving her ingenuity and creativity. It was in this business that she met her future husband. They both wanted to go to America and boarded a ship during storm season.

They moved to Atlanta, where her husband got a job in Emory.

Friedlander’s local impact, including her presentations at the Breman, showed during a question-and-answer session. Many people stood up just to praise her.

“You should never despair,” Friedlander said when asked what she might tell children. “Even when things look so gloomy and rather hopeless. Because somehow or other, there is a solution.”

comments