Suitcase to Survival

By Cole Seidner

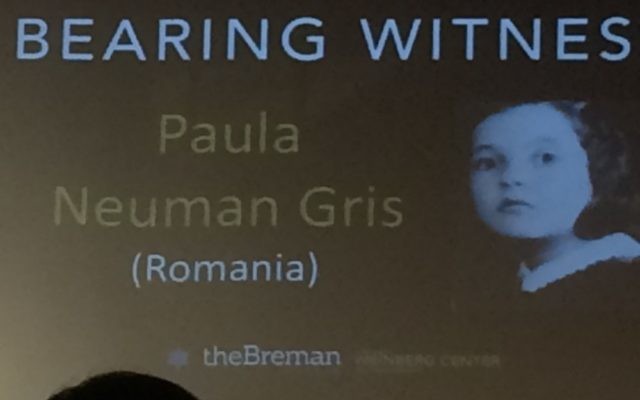

The crowd to see Paula Neuman Gris speak leaked out of the announcement hall, and people gathered in the lobby to watch on the TV screen there, including many who were there as Gris’ friends.

Her story Sunday, Jan. 17, during the latest installment of the Breman Museum’s “Bearing Witness” series began with the birth of her sister, Sylvia. A curfew limited the times when Jews could leave their homes, but her mother, Etka, went into labor at night. In an act of rebellion, amid labor pains, she went through the streets, risking arrest or being shot, to reach her Jewish midwife and deliver her baby.

“In the morning, she wrapped the baby up in the blanket that she had brought and walked back to the house. And there I was, standing and waiting for her,” said Gris, who herself was still a toddler after being born in 1938. “I think it was probably the last time that I retained some kind of sense of childhood in me. Until the end of the war, my mother and I were in a partnership. We were in a partnership to stay alive and to keep this child alive.”

In 1941, all of the Jews in Chernovitz, Romania (now part of Ukraine), received the order to pack their bags and be ready to leave. The order stated, under a directive to “cleanse the Earth,” they had two hours to pack two bags, and they would leave. Gris’ father, Simon, had been hauled off as slave labor by the Russians in 1940.

Her mother realized she could not pack two bags because she needed one hand to carry the baby. So she packed one, hiding money and papers in the corners and jewelry to bargain with someday, and they left.

“Our little blue suitcase is the only thing that we have that came from our home in Chernovitz and traveled with us through a series of places until it landed in a glass case at the Breman Museum in Atlanta, Georgia,” Gris said. “She packed into that suitcase some photographs, some documents that she thought would help us to get out of there or help her to somehow find my father and ransom him out. She packed some diapers for the baby, a towel, some soap.”

Gris thinks she asked whether they could pack her blanket or her bear, but her mother said no. Instead, Paula had to carry a soup can.

That was the last time she cried for years until the war was over.

“The most frightening thing for a small child is to know that they have no power and their mommy has no power either. Their mommy has no power to protect them or to protect herself,” Gris said.

It was November 1941 when the order came to transport the Jews to Transnistria. The cattle cars were filled with people who only wanted to go home. It was the coldest winter, and just getting there produced a high mortality rate from the cold and the fear.

Her mother got a small paper that allowed them to stay in the ghetto for nine months, delaying their deportation until June 1942.

Transnistria was very different from Auschwitz. Gris reiterated the message that the methods used to destroy millions of Jews differed from country to country, with Auschwitz highlighting efficiency over the weathered ways of Transnistria.

Her mother worked in a rock quarry while Paula and her sister learned to hide and stay quiet. They waited for their mother to come home, then waited for morning. Every day was fearful. There was no energy to play hide and seek because the “fear made people lethargic.”

With her final words before signing copies of her book for people, Gris said that had she stayed another month, she has no doubt that she would have died there. Instead, she, her mother and her sister survived the war and escaped to the West.

comments