Shema Yisrael: A True Judge?

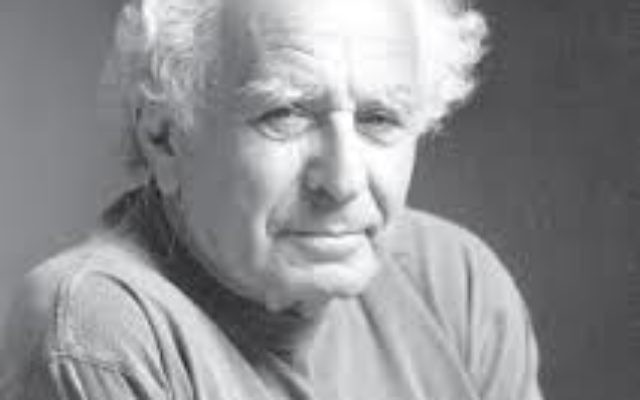

One Man’s Opinion by Eugen Schoenfeld

Unlike all other holidays in the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur is a holy day but is not a holiday. For unlike holidays, Yom Kippur is not a celebratory day.

With regard to other holidays, the Torah instructs us, “V’samachem bechageychem,” commanding us to rejoice in our holidays. But we are told that on Yom Kippur we should do the opposite: We are instructed to make our souls suffer.

In my shtetl of Munkacs in the Carpathian Mountains, where I was born, Yom Kippur was a joyless and fearful day. I would call it the day when the community sighed, sobbed and cried.

Just as the chazzan began to chant Kol Nidre, the sound of sobbing and crying began.

“Oy, Master of the Universe, write us into the Book of Good Life.”

“Please, Master of the Universe, give us a year of freedom, a year of health and a good economic year of sustenance.”

Those were some of the words that rose from the congregation.

Central to Yom Kippur was the belief in judgment and punishment. Most men in the synagogue would lift the tallit over their heads, and in the ensuing privacy and with trepidation they would chant Rabbi Amnon’s prayer that reminds all of us that this is the Day of Judgment.

On this day everyone is judged and sentenced: who shall live and who shall die, who will succeed in the coming year and who will not.

Unfortunately, our religion has instilled in us the idea that suffering is a consequence of violating G-d’s commandments. One of the first truisms that I was taught as a child was not the love of G-d, but, to the contrary, a passage from the Book of Proverbs supposedly written by King Solomon: “The beginning of wisdom is the fear of G-d.”

I further took it for granted that the Mussaf prayer is true when it states: “Because of our sins we were exiled from our land.” We, the Jewish collective, were punished for our sins.

But the years of the Nazi occupation of much of Europe during World War II forced me to question how G-d can hold us accountable for all the circumstances of our lives.

This became particularly clear to me in the fall of 1944 as I worked in a Nazi slave labor detail. I was helping to build a factory for the manufacture of jet planes with which Hitler intended to continue his conquest of the world.

I was Schutzheftling No. 90138. Dressed in a striped cotton uniform, with my number and a yellow triangle sewn on it, I was working with a group of other Jews on top of a parapet. The long poles we held jabbed at the freshly poured cement.

Suddenly, a man I knew from my hometown, a devout man, a rabbi, who at an earlier time had spoken of his fear of G-d, declared quietly to us: “Jews, according to my calculations, today is Yom Kippur. Let us pray.”

And so we did.

Every person in his own way contributed what he could remember to our prayers on that terrible day of Yom Kippur.

But now I had come face to face with some of the questions that were no longer thoughts encountered in the relative comfort of the synagogue.

Isn’t G-d violating His own description of Himself as a just G-d? Did He lie to Abraham when He declared that He would not destroy the righteous together with the unrighteous? Can He be the true judge that we declare Him to be on this Day of Awe? Well, is He a true judge or not?

Somehow, I survived that Yom Kippur.

A year later, with World War II at an end, I was a free man. But the thoughts of that day are still with me, and they still resonate 72 years later.

My thoughts, about G-d’s responsibility to us and our responsibility to G-d, are still at the heart of my understanding of what it means to be a Jew.

Eugen Schoenfeld will speak on his thoughts about divine responsibility during the Yom Kippur service at Shema Yisrael — The Open Synagogue.

comments