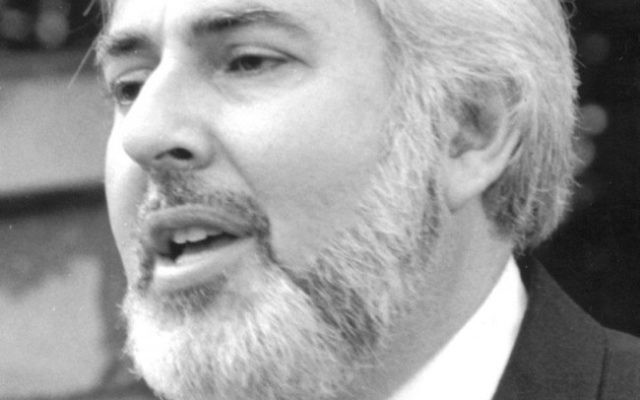

Shalom Lewis: As the Seder Turns

By Rabbi Shalom Lewis

As the years pass, there are constant reminders that we are aging. At first, we ignore the gentle signs of a receding hairline and crow’s feet. But as time progresses, the omens pile up with an unforgiving relentlessness. Huffs and puffs. Aches and pains. Social Security. Medicare. Black balloons and cemetery plots.

Nature is remote yet alerts us every moment of every day that we are closer to the final gasp than we are to the first breath. We all know this instinctively and manage a chuckle as the pages tumble from the calendar, confident that our fate is still decades away.

As I ponder such markers with the approach of Pesach, I realize that this labor-intensive holiday also serves to inform us of the direction and destiny of our lives.

As a child, though I was taught Pesach was Zman Cheruteinu, the festival of liberation, I found myself pressed into unwilling servitude. The maror, the salt water, the charoset — all the symbols of oppression, applied not to the Israelites but to me.

The kitchen was cleansed of all chametz. Sterilized with boiling water, feathers, a candle and a wooden spoon. Everything that was upstairs went downstairs. Everything downstairs came upstairs. Pots. Pans. Bowls. Utensils. Trays.

It was an exhausting undertaking. The delicacies all made from scratch. Nothing boxed or packaged (except matzah and almond kisses) was served. Shortcuts were sacrilegious, prohibited and a betrayal of tradition.

But as the years passed, I noticed a subtle shift in the Pesach prep from those exhausting days of yesteryear. As my parents aged, shortcuts became kosher lePesach, and tradition became more flexible. Cabinets weren’t emptied but taped shut. The countertop housed the stuff from the basement. Manufactured food was permitted.

And then, as the gait slowed and the energy diminished, disposables graced the Pesach table, and the food, purchased from caterers, was served in tin pans.

I marveled at the mutation and simplification of Passover as the years accumulated. The change told a story beyond the narrative in the haggadah. But the shift went beyond the culinary to the sacred ritual meal.

Sunrise, sunset, swiftly fly the years from asking the ma nishtana to answering it. From hiding the afikomen to paying for it. From grape juice to Manischewitz. From falling asleep at the table to leading the seder. Through the prism of Pesach I observed the seasons come and go and was reminded that we are ephemeral beings, changing, aging, and moving, unavoidably, toward the end.

And yet in the midst of this melancholy confession, there comes a gem that offers comfort and cheer as we confront a wrinkly, wobbly Pesach.

In the last pages of the haggadah we chant Chasal siddur Pesach — the seder has now ended — and yet there are still more pages that follow. And on those pages, significantly, are songs and melodies. When we think it’s over, we must realize that there are still songs to sing and melodies to compose. The end is an illusion. A tease, followed by lovely sentiment.

But what if the text is gently, softly teaching us about life itself — that finality is a myth, followed by more beauty, and we need not despair in the dusk? Pesach is a holiday and a metaphor. The seder is a meal and a message. The end is a moment and forever.

From infancy to dotage we are witness to the cadence of life. It twists and it turns, but it takes us, always, to a place of music.

Rabbi Shalom Lewis, the senior rabbi at Congregation Etz Chaim, will transition to emeritus status this summer.

comments