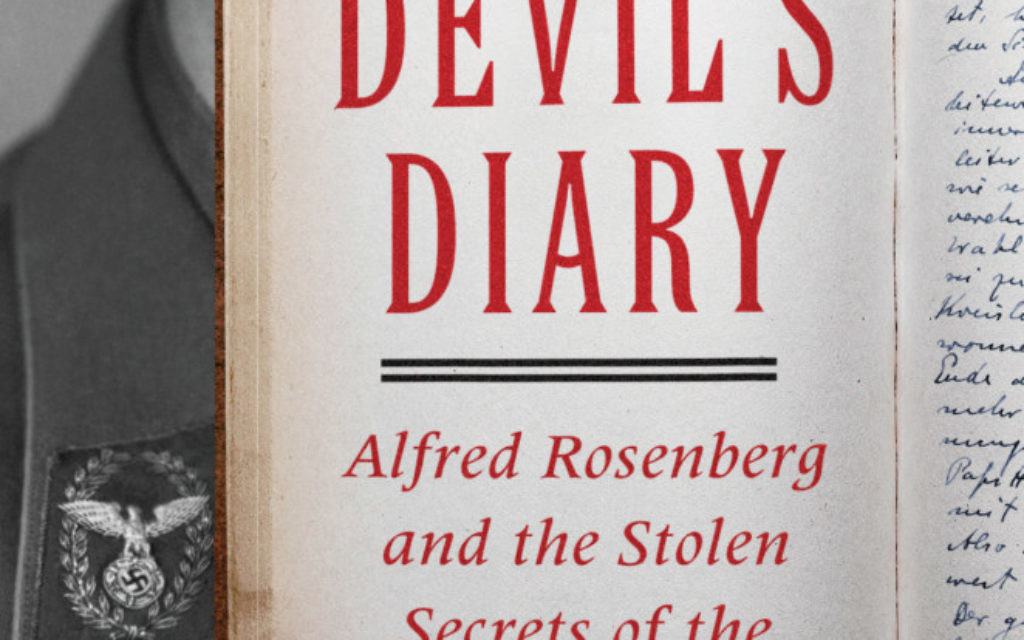

Review: “The Devil’s Diary”

“The Devil’s Diary: Alfred Rosenberg and the Stolen Secrets of the Third Reich” is a Holocaust history full of mundane surprises, starting with the fact that Rosenberg, despite the Jewish-sounding name, was one of the Nazi war criminals executed at Nuremberg.

Rosenberg, the devil in the name of Robert K. Wittman and David Kinney’s book, lived up to the title. He provided the pseudo-intellectual case for Nazism, for the concept of an Aryan master race and for the necessity of cleansing Europe of its Jews. He was hand-picked by Adolf Hitler to lead the party during Hitler’s imprisonment after the failed 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. He helped pillage the intellectual and artistic wealth of European Jews. He oversaw the administration of the lands the Germans tried to seize from the Soviet Union and thus played a direct role in the slaughter of millions.

That Rosenberg is not a household name alongside the likes of Goring, Goebbels and Himmler is largely the result of two factors: He was a colorless, bland, widely disliked man whose voluminous writing bored people senseless, and his damning diary of a decade of the Nazi rise and fall disappeared at Nuremberg.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

That disappearance was the work of the second main character in “The Devil’s Diary,” Robert Kempner, a World War I veteran and lawyer who was ousted as a high-ranking bureaucrat in Berlin in 1933 because of his Jewish parents, then returned to Germany in triumph as an American citizen serving on the prosecution team at Nuremberg.

Kempner stole more than 400 pages of the Rosenberg diary, along with tons of other documents, and shipped them home to Pennsylvania. His likely motive was to use the papers to write his own history of the Nazi regime from the perspective of one of its victims.

He wanted to be sure the story was told right, but instead he managed to bury the evidence and the significant role of Rosenberg for more than half a century.

How the diary and other documents resurfaced and found a home at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum serves as an extended prologue to the book, which tries to tell the Nazi history as a dual biography of Rosenberg and Kempner.

It’s a difficult task because both of the main characters are repellent. Rosenberg is, of course, a monster, but Kempner is a self-aggrandizing, womanizing egotist who abandons teenagers in his charge and leaves his own sons behind to make his escape to America, spreads false stories in the press about his exploits, and undermines efforts to document Nazi crimes.

Wittman, an FBI veteran at finding stolen treasures who helped recover the Rosenberg diary, and Kinney, a veteran journalist, do a good job of weaving together a readable narrative, but despite the eye-catching title, their book has little new to offer. Rosenberg’s secrets consist of details about the infighting among Hitler’s lieutenants and reveal Rosenberg’s increasing separation from the real power and decision-making.

In the end, “The Devil’s Diary” requires a lot of reading for a slight gain in Holocaust knowledge.

comments