Poetic Love Blooms in Frozen ‘Fever’

Holocaust stories with happy endings aren’t common, and those that try to find some ray of hope usually fail in the effort. “Fever at Dawn” is the rare exception.

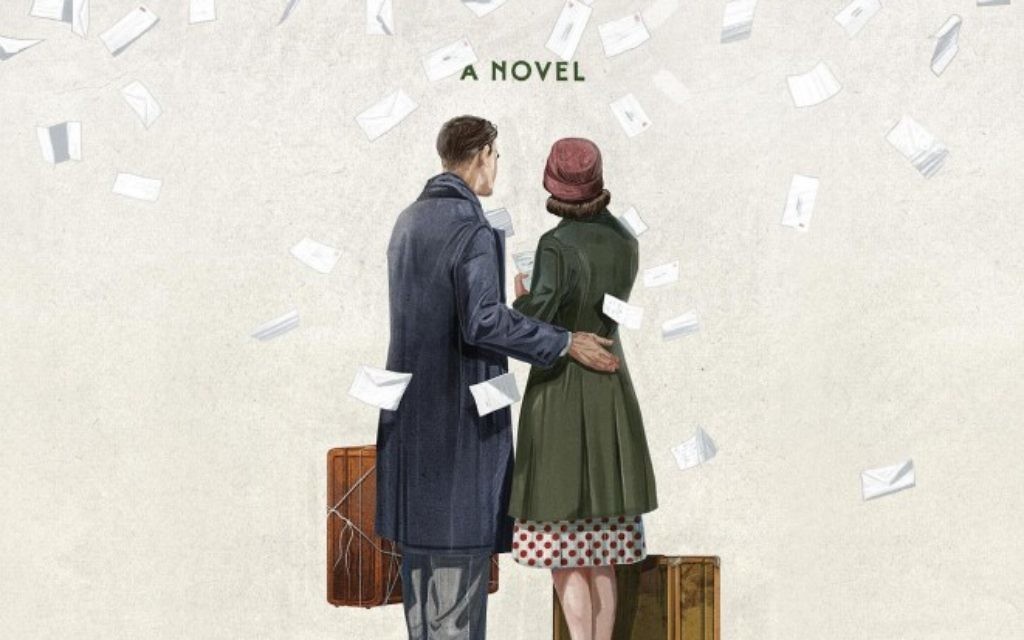

It’s a lightly fictionalized version of how Hungarian first-time novelist Péter Gárdos’ Holocaust survivor parents met and fell love — inspired by his discovery after his father’s death half a century later that they had kept their love letters all those years.

Miklós and Lili grew up in the same part of Hungary and — in parallel, without ever meeting — were rounded up as young adults and sent to the Nazi camps in 1944. Both managed to hang on and were liberated in 1945 at the hospital at Bergen-Belsen, then sent to recover after the war in different parts of Sweden, where Gárdos tells his tale.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Miklós has tuberculosis, and his Swedish doctor, who speaks broken Hungarian because he has a Hungarian wife, tells him has no more than seven months to live. Miklós, however, is an optimist and knows the diagnosis must be wrong.

He procures the names of 117 young refugee women from the area of his native Debrecen and writes a letter to each of them, happy to find some friends and hoping to find a wife.

One of the 18 women who reply is Lili, who is suffering her own postwar ills, though nothing expected to be permanent. She doesn’t plan to answer Miklós, but during a period confined to a hospital bed, she has nothing better to do.

Gárdos weaves a half-year of their correspondence through the story of how they each deal with the bureaucracy of Sweden, the Red Cross, and the distant, newly socialist homeland they plan to return to.

Obstacles naturally arise, from Miklós’ terminal illness to the bitter Swedish winter and from a jealous friend of Lili’s to her flirtation with Catholicism, all while they support each other from a distance amid the emotions of the search for surviving relatives in Hungary.

Gárdos, a filmmaker who released a movie version of the story in December, four months before the book arrived in the United States, has a wonderful, straightforward prose style. Translator Elizabeth Szász deserves credit for capturing his subtleties in English, particularly the struggles the characters have communicating through Swedish, Hungarian and German.

Portraying two simple people who have lost everything, Gárdos keeps their actions, descriptions and motivations simple, allowing the important details — a ragged piece of tweed for a coat, the metal dentures replacing Miklós’ smashed-out teeth, his careful handwriting, her love of the piano and embarrassment at the small silver crucifix given to her by a Swedish family — to bring them to life.

For example, in a real-life touch, Miklós is an avid socialist and is determined to educate his new love on the movement he is sure will make the world a better place for all. It is his devotion to socialism that enables him to go along with Lili’s plan to convert to Catholicism and, encouraged by a Swedish rabbi, to get married under a chuppah instead: He simply doesn’t care about religion.

But Gárdos doesn’t let a sweet love story devolve into a political screed. Instead, the touch of socialism lets us see that Miklós is an idealist and that Lili, even though younger and less educated, has her feet strongly enough rooted to the ground not to buy any of the political nonsense. We also understand the attraction Lili, who has rejected her faith, feels toward Miklós’ ability to maintain such a strong belief in anything after all they’ve been through.

It’s the same attraction their story holds for readers lucky enough to get a glimpse into their lives.

—

Fever at Dawn

By Péter Gárdos

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 232 pages, $24

comments