Keret Opens Weber Eyes to Absurd Side of Life

Etgar Keret began writing during his compulsory service in the Israel Defense Forces, but he said the continual conflict faced by his country hasn’t been a major influence on his work.

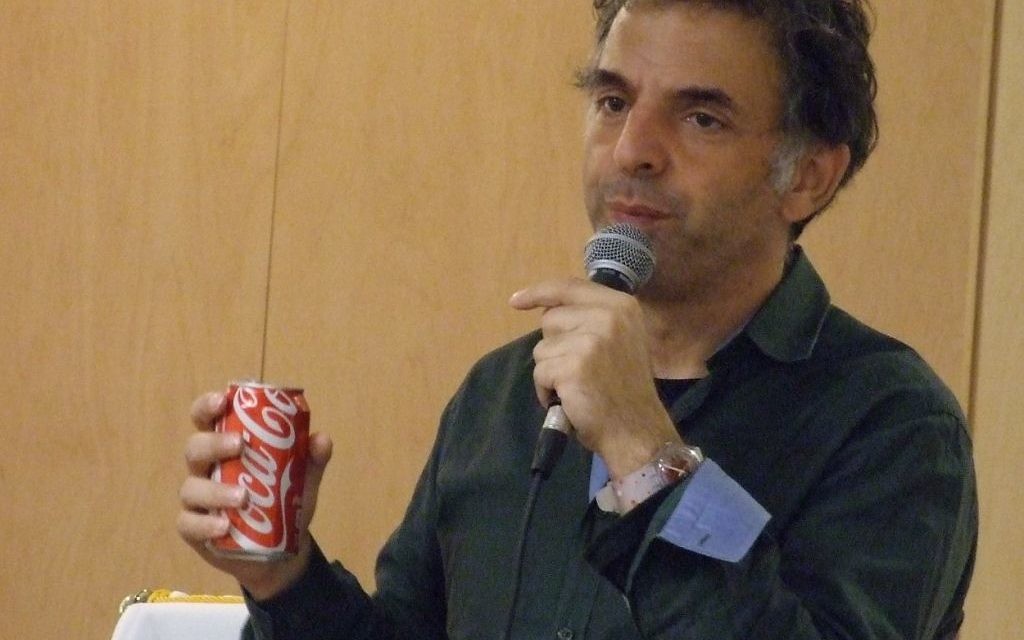

“Israel is in the background, but I’m not really writing about Israel,” Keret told Weber School students Wednesday, Oct. 21, during his third visit to Atlanta in a year. “Personal things affect my writing more, like becoming a parent.”

Having held a discussion with a select group of students in Hebrew, Keret talked in English with much of the student body. After reading his short story “The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be G-d,” he answered student questions that tackled serious topics about his influences, processes and mental state but, like the writer himself, remained playful.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

When students were slow to show the bravery to ask the first question, for example, Keret skipped it: “OK, who wants to ask the second question?”

Keret is attracted to the absurdities in life, such as something he pointed out during another appearance that night at Congregation Or Hadash: He has realized how much he loves spending time with his family and made that a key theme of his latest book, the memoir “The Seven Good Years,” released this summer. So now he travels around the world to read from that book, pulling him away from his son and wife so he can declare how much he cherishes time with them.

Another absurdity is the house he owns in Warsaw. An architect built it as a gift for him and designed it to match his short stories — narrow but deep. So the house is only about 3 feet wide, setting a world record, but is two stories and has all the facilities of a normal house. He called it a “quirky attraction” he visits occasionally, sometimes spending the night.

“I think that life is very absurd and strange,” Keret said. That’s why his stories seem absurd. “When I write stories, I want to show life as it is, and for me it’s very strange.”

One strange thing is his place in the Israeli high school curriculum, about which Keret expressed ambivalence. When he was first added, he said, he got a letter from a teenager suggesting that Israeli authorities were unhappy with his popularity among the young, so they made him part of the curriculum to force students to read his stories — thus ensuring the kids would hate him and never read him for pleasure.

Keret delved a bit into his views on writing. He said he doesn’t believe in stories but in readings, which mix the text and the reader. Each such relationship is different, so his stories are different for each reader.

His stories have been translated into more than 30 languages — “The Seven Good Years,” which has not been published in Hebrew to provide a bit of protection to Keret’s son, has just been translated into Farsi to be smuggled into Iran — and he acknowledged that something always is lost in translation.

He said translations are actually double translations: Any writing represents a translation from emotions to words, so a translation into another language makes the work twice removed from the source.

Keret acknowledged having a depressive side and said he spent much of his childhood staying home alone from school because his Holocaust-survivor parents feared letting him walk the streets. He said he still spends a lot of time alone, “but I yearn to be with people to compensate.”

It’s perhaps not surprising then that the author he sees as his greatest inspiration is Kafka, who gave Keret hope of being able to write “as stressful,” if not necessarily as well.

comments