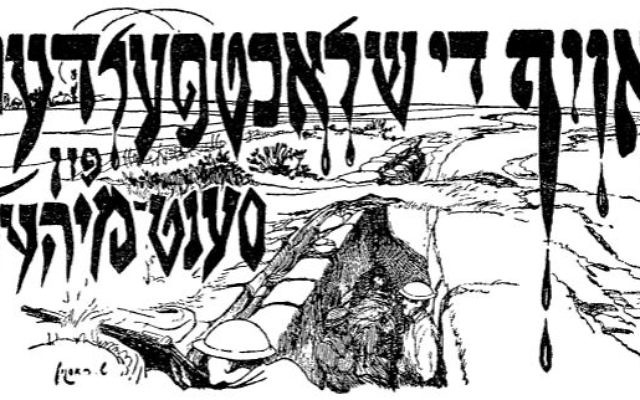

Jewish Soldiers Found Joy in 1917 Georgia

A Yiddish speaker training at Camp Gordon wrote about Chanukah, Zionism and the Atlanta community.

The following is an excerpt from the “Oyf Blutige Vegen” (“On Bloody Paths”), the Yiddish-language World War I memoir by a Jewish man from New York named S. Cohen. The book was first published in 1923 by Meizel’s Publishing in New York, although it included material published in the newspaper Der Tag in 1918 and 1919 and in Zeit in 1921. Cohen, who dedicated his book “to my dead and to my living comrades who fought and believed,” trained at Camp Gordon in 1917 and 1918, long enough that he celebrated both Chanukah and Passover in Atlanta. He estimated that 3,000 Jewish soldiers were at Camp Gordon with him.

This excerpt comes from Dan Setzer, who recently completed what he believes is the first English translation of the entire book. His translation is available free as an e-book and a PDF file at dansetzer.us/cohen.

The only place the Jewish soldiers could go to seek out their brothers was on Friday evening at the “services” which were run in the spirit and format of the Jewish Welfare Board in an auditorium of the Young Men’s Christian Association. The spirit of this organization toward Jewishness and folklore has already been described in the Jewish press. It is enough to say that we in Camp Gordon were in the same situation as in the other camps.

We came every Friday evening seeking our G-d in order to warm our Jewish feeling and soul, and found an experience without a face, without meaning. A dry “service” and a sermon that you could guess what the content would be ended our service to G-d. Usually we came away from such Friday evenings deflated and felt just as miserable as we did during the rest of the week from drilling, if not more so due to the bitter disappointment.

We did get some comfort from the contacts we had with the nearby Jewish community in Atlanta. It is simply a wonder where all of the brotherly love came from that they showed us. The best of all was that it was not being done through institutions or parties but rather from individuals.

Rich or poor, they came to the Allies Progressive Club in the Zionist shul, where the Jewish soldiers could come together and do a lot to chat and create a homey atmosphere for the Jewish soldiers. They took men into their homes for the few free hours we had. Through the loving and intimate contact from the whole household, they got close to those people, just like they were old friends.

As soon as we got back from Atlanta, it all went away, and we once again felt miserable and lost in the huge camp and felt even more intensely the emptiness of the Friday evenings. Fewer and fewer soldiers came to the “services,” and it appeared as though the little bit of Jewish life in the camp might wither and die if it were not for the past and active Zionists and Zionist workers.

Once when I went to Atlanta, going into the Allies reading room, I found the usual small groups of intellectual Jewish soldiers huddled around newspapers and books. In a neighboring room they were divided up along the usual party lines as in civilian life: for and against Zionism due to the Jewish Congress, relief questions and so forth.

It was an unusual sight to see men gesticulating and arguing in a pure Yiddish while wearing Uncle Sam’s uniform. Among the debaters, one’s striking appearance stood out.

A strapping young man with a prominent forehead and gray, earnest eyes. With his loud voice and Litvak accent, his voice dominated the others when he yelled: “Assimilated is what you are! You are a scourge on the Jewish folk!”

On the way back to camp, we rode together and made plans about starting an organization, a national club for Jewish soldiers, and we even made up lists of the people we would invite to the initial planning meetings.

The next evening when I went to Odess’ barrack, several of the gentile soldiers came at me, calling out: “Odess! Another Jew is coming!” “He wants to organize a Jewish army.” “Send them to Jerusalem.” “Better yet, give them some pushcarts.”

I saw some friends and acquaintances sitting around Odess’ bunk. They belonged to other regiments and other organizations. Odess quieted us down. They respected him because he showed so much commitment to the Jewish community.

Then we got down to the task at hand. First we wrote down a platform, which read something like this:

Name: National Club for Jewish Soldiers

Every Friday evening after the services in the YMCA, Building 151, Jewish readings, declarations and so forth.

Agitate for the Allies, particularly for the Balfour Declaration. Support all Jewish works such as Zionism, relief and the Jewish Congress. Spread Jewish news among the less informed or Americanized Jewish soldiers.

One of Odess’ friends, a Christian sergeant, listened very attentively to our discussions, and when Odess at the fellow’s request explained to him all that we were talking about, he sat with us for a long time, acquainting himself with these Jewish issues.

Finally, he said, turning to us all and pointing to the camp’s Christian soldiers, mostly Polish and other immigrants: “Don’t mind them. They aren’t true Americans.”

In the coming several days we continued to pursue our goal. The two welfare board members, Mr. Ross and Mr. Ginsberg, at the beginning looked askew at our organization. They pointed out that we did not know how the men “up there” would take to the idea, but we explained to them categorically that we wanted to express our Jewishness according to the way we understood it, and the first thing we wanted to do was to hold a Chanukah evening, and they gave in.

The feelings in the camp for one of the “welfareniks” slackened somewhat when he advised us how to get along with the Christians. He said: “I have gotten along well with the Christians, and do you want to know how? Throughout the four years I was in college, they never knew if I was Jewish or a Christian.”

Chanukah in Camp

The joy of the club members when we learned that finally we were going to take the first steps was indescribable. They started getting ready for a big holiday with extraordinary enthusiasm and love.

Then came the long-awaited Friday evening, the 14th of December, and as soon as they came into the auditorium of the YMCA, Building 151, they could see the amazing difference: The auditorium was packed to overflowing.

In addition to the benches, which were full, every other available place was taken, right to the walls. On the stage was a beautiful menorah which had been brought in from Atlanta and was shining brightly. Even brighter sparkled and beamed the faces and eyes of the onlookers.

The evening was introduced by a representative of the welfare society, Mr. Rom, who had been leading the Friday ceremonies. Then he introduced fellow member S. Adam as the chairman for the evening.

Mr. Adam made some very cordial comments about the Soldiers’ Club, which had committed to do all the work in order to nationally promote a revival and well-being for the Jewish people and also mutually for the Jewish soldiers’ welfare. After that, he spoke about the meaning and the story of Chanukah.

His later remarks about the English declaration called forth great joy and elation from the audience.

The opening ceremonies continued with fellow member Genet, who sang the American song of praise. Member Schwartz played the song “Hope” (“Hatikva”) with piano accompaniment from member Blum. The audience stood as one man and sang along. It made our hearts joyful to hear the strong, young voices singing songs of hope.

In the tones of “Hope” that we sang that night, we heard a powerful cry of freedom from a people who had waited such a long time for freedom. We did not want to break off from singing this Jewish hymn, which we repeated again and again.

Then member Ravitz blessed the Chanukah candles with the true bent of a Jewish cantor. Member Kranik sang “Eli Eli.” Member Green recited “Cup” by Frug and “Jewish Freedom” and “The Little Light” by Morris Rosenfeld. Member Schwartz, an industrious student from Priochnikov, played “Moishele and Shlomele” by Hayim Nahman Bialik on his concertina. A. Fogel read “Nerves” and “Chanukah Gelt” by Sholem Aleichem.

Members Pavel and Karp sang the “Song of Exile” and “Mamenu.” “Amerika” was sung by members Schwartz and Blum with a concertina accompaniment. The evening closed with the singing of the Workers’ Zionist Oath.

For a long time people could not tear themselves away from the hall and the people with their many dear and beloved brothers.

Finally, we had to go back to the barracks, which were miles away, before lights out. Groups dispersed in all directions, and in the stillness of the night you could hear the Yiddish voices calling out “Shalom Aleichem,” hearty laughing, the sounds of “Hope” and also the sorrowful tune from the song “Oh Oh Mamenu!”

You could hear a mournful voice, which was all the more poignant in the stillness of the dark night.

A puzzled guard with a rifle on his shoulder showed himself, looked at the unusual group, then went away disappointed into the darkness back to his post, undoubtedly thinking to himself, “What’s with the Jews?”

And the Jews returned to their barracks but took a long time to get to sleep. Thousands of thoughts and feelings were crowding into the heads of the Jewish soldiers. A happy Friday evening and many joyful eyes had a hard time closing.

That is how we celebrated Chanukah. It is also interesting to note that the Welfare Board members were unusually surprised with the success. They saw what the people wanted, and they promised to do everything in their power to help.

Above all, it was the newcomer, S. Zuckerman, who had with his sincere brotherhood drawn us all in.

Our first attempt with Chanukah had convinced us that the Jewish soldiers longed for a homey atmosphere and were ready to work to create it, even in camp, in spite of it most times being very hard to do so. …

Some of the non-Jewish soldiers made a few innocent comments like “I hope the Army doesn’t become Jewish like New York.”

The weaker Jewish soldiers were frightened and shrunk back, lying low for a while, but it was enough to go to them with the magic words “Come brother!” And He came with outstretched arms and with a burning flame of love for his people and their dreams.

comments