Iranian-Jewish Refugee Sees Parallels With Muslims

Before fleeing Iran, Hengameh Pourfakhr says, she was one of many minorities persecuted in the country.

Walking through the streets of Shiraz one day, Hengameh Pourfakhr and her friends were scolded by a basij officer for laughing in public. The encounter was the last straw for Pourfakhr, who packed her suitcase and fled Iran.

For a Jew, Pourfakhr said, “there was always an undercurrent of anti-Semitism in Iran, depending on what period in history you looked, where you lived and what echelon of society or economic rival you were associating with.”

She said those who were affluent or highly educated were not as anti-Semitic as the uneducated segment of society.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The official stance in Iran was respect for the people of the book, including Jews, who were allowed to have their own schools and had synagogues. On the surface, it seemed Jews were not persecuted, but the anti-Semitism was still sensed, she said.

Pourfakhr recalled that her father would frequently hear comments at work such as “Hey, you’re a Jew. Why are you our boss?”

The Islamic republic implemented more oppressive laws after the 1979 revolution. The hijab became compulsory for women, even for Jewish women like Pourfakhr. She said, “As a woman, I felt like a second-class citizen or someone who is looked down on and not equal to men.”

After she graduated from high school, Pourfakhr sought to study physics at an engineering school overseas, but her dreams were dashed when the Iran-Iraq war broke out in 1980. The Islamic regime refused to issue passports to Jews.

Life in Iran became more dangerous, especially for religious minorities, Pourfakhr said. “Anyone caught speaking against the government was thrown into prison.”

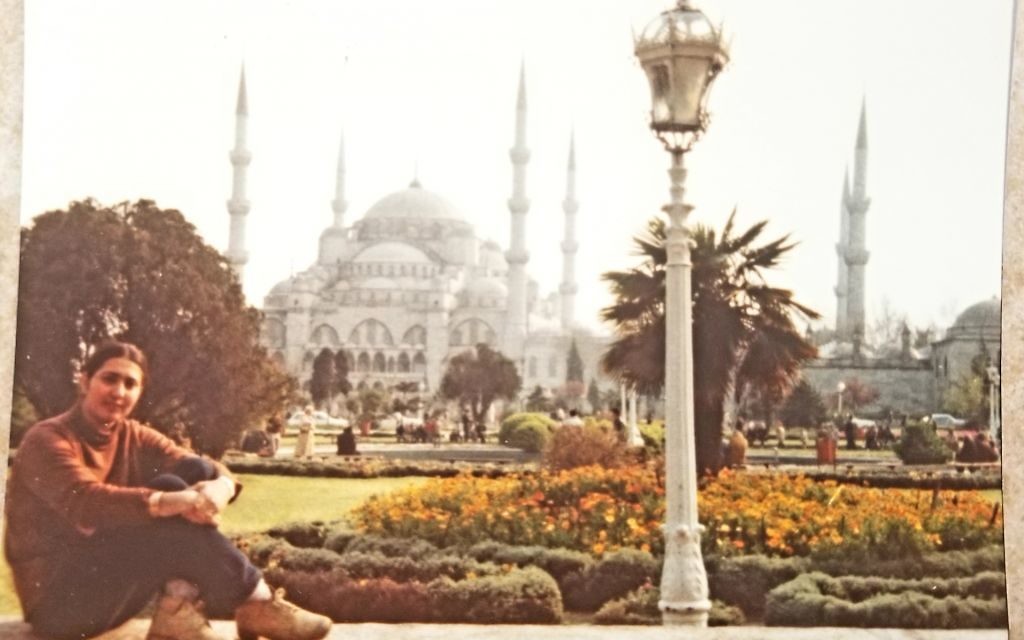

As a last resort, Pourfakhr’s family hired an Iranian Kurd to smuggle her across the Turkish border.

Once Pourfakhr arrived in Turkey. a rabbi from Baltimore sponsored her trip to Switzerland, where she obtained a passport from the Red Cross and a visa from HIAS that granted her refugee status. She traveled to Vienna, where she began babysitting in exchange for room and board.

It took Pourfakhr almost a year until she landed in New York with a suitcase filled with clothes, some jewelry her parents had given her and $200 in her pocket. In her first few days in Manhattan, Pourfakhr spent time exploring the city until the New York Association for New Americans (which no longer exists) located an Iranian family she could visit for Shabbat.

Meanwhile, because her father was interrogated by Iranian officials after her departure, Pourfakhr couldn’t get any money from her parents and was forced to make it on her own.

She relocated to Brooklyn and was granted room and board by an Orthodox family in exchange for babysitting six children.

Pourfakhr studied physics for two years at Brooklyn College, then was accepted into Stony Brook University’s engineering school. Before her husband moved to Atlanta to be with her, Pourfakhr shared a room with another Iranian and landed a position at the Southern Co., where she still works today.

Pourfakhr noticed that there weren’t many Jews or Iranians at her new job. “People always asked me, ‘Where are you from?’ And when I told them I’m from Iran, they always assumed I was Muslim,” she said. “They were always surprised to learn that there were Jews in Iran.”

But the inquiries did not bother Pourfakhr. “I took pleasure in trying to educate them, and contrary to what they thought, I told them we don’t ride camels and actually live in big cities.”

Pourfakhr has connected with community members in Atlanta and belongs to Temple Kol Emeth. She said she has been able to maintain her Iranian heritage and Jewish religion but noted that some Ashkenazim still don’t know about Sephardic culture.

Pourfakhr said she owes her life to a number of Muslims who helped her escape Iran, and she supports immigration from predominantly Muslim countries because many of their residents, such as Iran’s Baha’i community, suffered similar persecution.

She added, however, that anti-Semitism is embedded in some cultures and that people will sometimes hang on to those beliefs. “I have a lot of Muslim -Iranian friends in Atlanta who still carry anti-Semitism and anti-Israel sentiment, even from those who don’t have anything against Israel or Jews,” she said. “But it’s more of a political stance rather than anti-Semitic.”

Pourfakhr said one of the reasons she loves living in the United States is because of its diversity and respect toward unique backgrounds, cultures and religions. “I believe that when you bring people out of that culture in the Middle East into an open environment which teaches respect, then you erode that ignorance.”

comments