Innovative Techniques Help People Trace Ancestry

Gary Palgon offers some tips individuals can use to trace their genealogy on Dec. 3 at the Breman Museum.

Gary Palgon has worked on genealogy since he was 13 and traced his family to the 1600s in Lyakhovichi, Belarus. He expanded on his findings and offered the Jewish Genealogical Society of Georgia some techniques to create, access and analyze records Dec. 3 at the Breman Museum.

Palgon said amateur genealogists should first investigate what exists about the towns that interest them.

“You’re going to contact anybody and everybody to see if they have done any research on the foreign place, if they have a list of available records that exist, and if they know of any records or of any researchers,” he said. “I know this sounds obvious, but people often forget this step.”

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Palgon uses websites such as Jewishgen.org. “Before I scour for anything, I first put a list of people together who could potentially feed me knowledge and find information about my family.”

Palgon created a group of people interested in Lyakhovichi and retrieved some family trees and a photo of a Jewish burial procession. He said, “All of a sudden, you are building more than just a family tree of just names and dates, but begin to retrieve a story of how the people lived because that’s really what our personal history is.”

Palgon and his father traveled to Minsk in 1994 but never made it to Lyakhovichi because some people tried to steal money and passports from him. Palgon did, however, visit the national archives. He said the process can be sketchy, but you can hire someone to conduct research for you.

Having a list of available records and creating a catalog of existing documents are helpful, Palgon said. “You are just trying to create a catalog that will be of use. Having a list in place allows you to double-check anything you missed when forwarding it to other researchers.”

He said people should gather donations to hire a researcher or put together a group for projects. “The researchers are going through the records page by page, so wouldn’t it be easier on the wallet if you gathered your researchers and asked them to fund an effort which will help look for 10 family names instead of two?”

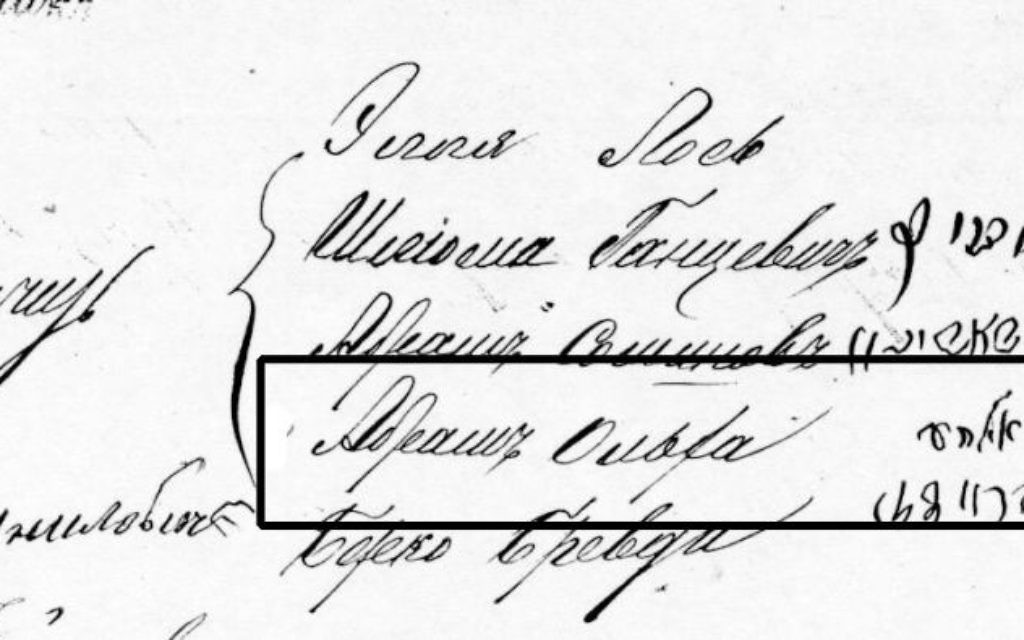

Through his research, Palgon retrieved an innkeeper’s census that told him about the people passing through the town, as well as a tax list from 1862 that mentioned a direct ancestor. Palgon also found some court records from 1864 that revealed that one family member’s request to move to Minsk was denied.

“While we first think of these documents in terms of birth, marriage, death, place and date, there is a story behind them which tells what was going on in that town at that time,” he said.

Once Palgon accessed the records, he worked with Neville Lamdan, a contributor to “Avotaynu,” to index the information and created a list of entries based on his surname. Palgon said Lamdan then compiled all the information and wrote a paper on what it was like living in Lyakhovichi as a Jew at that time.

“We have to look and dig into history to understand what those records look like,” Palgon said. “It takes a little bit of time and energy, but that’s your family history.”

comments