A Message for All Unjust Leaders: Hands Up

Hands are the heart of the matter in this week's parshah, Beshalach.

Your hands can make or break society. In the digital arena, where much of modern life plays out, your hands type and click. In the real-world arena, your hands cook, fold, drive, soothe.

Your hands cut surgically into bodies, pick up trash, plant orchards, build cities, lay tracks. Your handshake greets others and seals deals.

Just as your hands can connect people, they can also divide. Your hands can gesture rudely, bundle into fists or worse: They can go where they are unwanted and do unthinkable things.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The power of our hands is indisputable. Choosing how to use our hands is our task in every moment.

Hands play a vital role in this week’s parshah, Beshalach; the word for hand (yad) occurs at least 17 times. At times the word refers to actual hands, while at others it indicates the power hands wield.

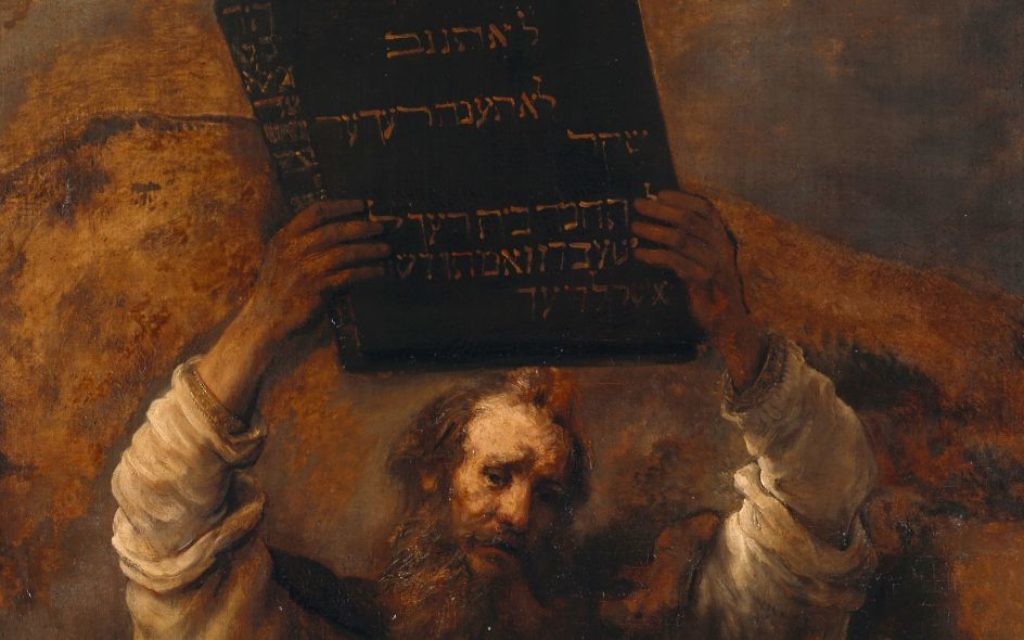

The hands it speaks of are Moses’, yet sometimes the parshah refers to G-d’s own hands, a few times to the hands of the Israelite people as a whole and once to Miriam’s hands.

The hands it speaks of are Moses’, yet sometimes the parshah refers to G-d’s own hands, a few times to the hands of the Israelite people as a whole and once to Miriam’s hands.

The most famous incident is when Moses holds his hand over the Sea of Reeds. The waters split, disclosing a dry path for the Israelites to flee Pharaoh’s pursuing army. When all are safe on the other side, Moses again raises his hand above the sea, sending it crashing back upon itself and drowning the Egyptians.

Miriam then takes a timbrel in her hands and leads the community in song and dance to celebrate G-d’s single-handed victory over the Egyptians.

Another popular scene is Moses holding his hands up while Israel battles Amalek. Israel, under Joshua’s leadership, falters when Moses lets his hands down but prevails when they are aloft.

Aaron and Hur take it upon themselves to give Moses a seat and assistance by holding each of his hands up and steady for rest of the day, enabling Joshua’s military success. G-d then instructs Moses to inscribe (by hand) a document that G-d will blot out the memory of Amalek.

The parshah ends with Moses building (by hand) an altar named Adonai-Nissi: “Hand upon the throne of Adonai — for Adonai will be at war with Amalek throughout the ages.”

It may comfort many that G-d’s hands continue to be active in this world, specifically in the tasks of eliminating sources of terror and harm. Yet I am more inspired by the first mention of hands in this parshah: “Adonai stiffened the heart of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and he gave chase to the children of Israel. As the children of Israel were departing with a high fist (b’yad ramah), the Egyptians gave chase to them.”

Can you see their hands held high, high in defiance of an unjust regime? This was then and remains today a powerful signal of social solidarity and of resistance to power gone awry.

Remember John Carlos and Tommie Smith, the black athletes who stood atop the podium at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, each with a gloved fist raised aloft, signaling their solidarity with the black power movement then sweeping the United States?

Carlos recalls: “I had a moral obligation to step up. Morality was a far greater force than the rules and regulations they had. G-d told the angels that day, ‘Take a step back — I’m gonna have to do this myself.’”

He continues: “The first thing I thought was the shackles have been broken. And they won’t ever be able to put shackles on John Carlos again. Because what had been done couldn’t be taken back. Materially, some of us in the incarceration system are still literally in shackles. The greatest problem is we are afraid to offend our oppressors.”

Raising our fists against tyranny may be scary, yet we must do it for society’s sake. Whether we are leaders like Moses, John or Tommie, whose hands everyone can see; or like Aaron and Hur, who support those visible leaders; or like Joshua’s soldiers, wielding weapons for a just cause; or like Miriam’s troupe building culture; or the masses in general — we are to raise our fists. We are to raise our hands in defiance of racial injustice no less than sexual predation.

In every age and in every society, may we have the courage, like G-d, to raise our hands against ignorance and arrogance.

Rabbi Jonathan K. Crane is the Raymond F. Schinazi scholar of bioethics and Jewish thought at Emory University’s Center for Ethics, an associate professor of medicine at the Emory School of Medicine and an associate professor of religion at Emory College.

comments